blog

Interview with photographer Aline Smithson

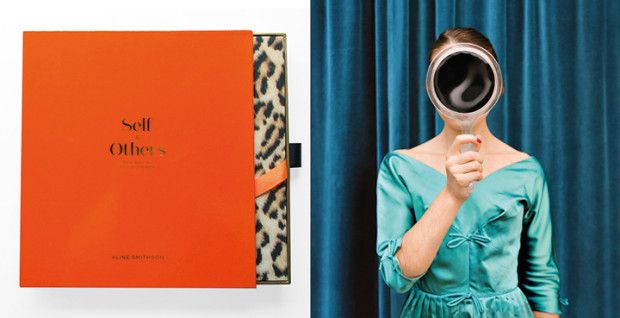

Self & Others: Portrait as Autobiography by Aline Smithson

Sarah Hadley: Congratulations on your Kickstarter success, your teaching award, and your book being published this year! You have also been producing LENSCRATCH every day for more than eight years, which is an incredible accomplishment. Engaging with so many photographers from around the globe and in the classroom, what trends are you seeing in photography and where do you feel photography is headed?

Aline Smithson: Thank you Sarah! It has been quite a year. Lots and lots of hard work, but ultimately exciting and wonderful.

I’m beginning to think there has to be a big seismic shift in how we make and present work. Most photographers have been working in the 20+-image project template, which ultimately constrains creativity. I certainly understand how the process of revisiting an idea over time in a specific way makes for a meaningful body of work, but now it’s become the norm, and to be honest, it’s gotten a bit stale. It’s important to consider creativity and these templates don’t always allow for it. In my opinion, that may be one reason why the photo book has become so important as it allows for new ways of considering photographic art. I’ve looked at hundreds of portfolios this year, between various reviews, Lenscratch, and jurying Critical Mass and I think it’s time to step away from the well-worn path to success.

On another note, I love the ever-expanding array of personal narrative projects, where ephemera is being combined with old family photographs, new capture, black and white mixed with color. It’s a form of story telling that fleshes out a more layered articulation. McNair Evans project (and book), Confession for a Son, is a perfect example of this. As photographers, we are now using the camera to look inward, and in some ways, using photography as an almost therapeutic expression for our lives. We are creating projects about ourselves, our identities, our families, using the camera to capture our interior worlds rather than just the outside world or what’s reflected in our viewfinders. We have become image-makers rather than image takers. This is a big shift from the days of simply shooting lovely landscapes and portraits.

SH: So many of your students have gone on to have amazing careers and while I’m sure they were talented and motivated, how did you help steer them? What do you feel is unique about your style of teaching and how has teaching changed you and your art?

AS: Photographic educators are the unsung heroes in the photo world and I just want to acknowledge how hard educators work to give students the tools to make significant work. I was amazed by the submissions to the Lenscratch Student Award this year, which definitely is a result of excellent and insightful teaching.

In my own classes, we spend a lot or time on the articulation of the work, discarding anything that feels false and work to connect the project to the person. I help them contextualize their projects and we brainstorm not only ways of working, but consider all aspects of presentation. I also consider myself an open book–sharing my failures, my experiences, and thoughts on the photo journey— and hopefully, I’ve helped them to not make the same mistakes that I did, and more importantly helped them understand the potential of their photographic voice. We have lots of discussions about the journey of a fine art photographer and always consider the bigger picture.

Emily on Zebra from Hollywood at Home

I’m sure it helps that I have the perspective of sitting at both sides of the reviewing table, which is beneficial to students. Also from writing Lenscratch and attending portfolio reviews, I also have awareness to the broad array of subject matter being produced and share that in the classroom. I too have so much more to learn and that keeps pushing me forward.

As for how teaching has affected me, it has forced me to synthesize what I am exposed to, understand and then articulate the contemporary photo landscape to students. Teaching has also helped me better articulate my own work. The down side is that teaching takes away time from being an artist. It’s required me to juggle a lot of balls on a daily basis, answering e-mails from current and past students, mentoring and tutoring photographers outside of the classroom, plus all the work behind Lenscratch, and the work of being a photographer…all of that makes any creative time to produce my own work so much more precious. I have learned to put big X’s on the calendar to set aside days to simply make work.

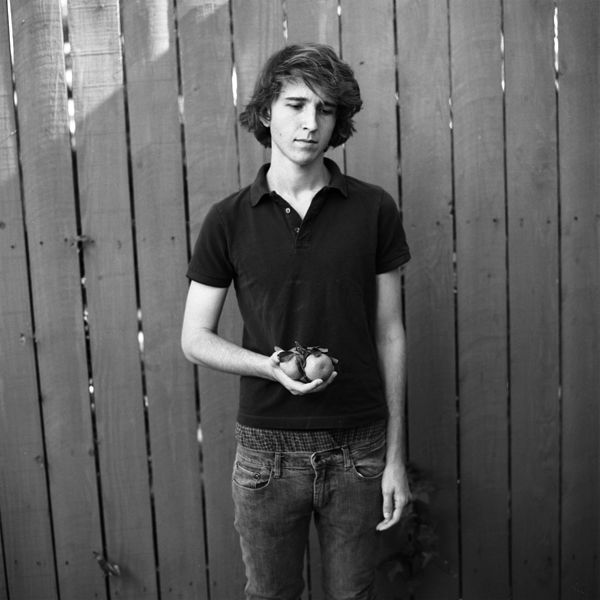

Henry with a tangerine

SH: You wrote a very honest piece about the high cost of being a fine art photographer from buying a good camera, taking workshops, entering juried competitions and going to portfolio reviews. How valuable have portfolio reviews and juried competitions been for you both as a reviewer and as a photographer? Do you think the art world favors those with resources or backing? What advice do you give those with little means?

AS: We rarely say out loud how expensive it is to be a fine art photographer. That cost limits who can participate in this arena and that really, really bothers me. Giving an expanded and diverse population a way to visually articulate their lives is a powerful thing and those are just the people who need photography the most. I do think that it’s possible to get work out into the world without spending a bundle, but not easy. Once I spent a year only submitting to magazines and to nothing that cost any money—submission costs had become too prohibitive and I needed a financial break. But at some point, one needs to get work on the walls and the printing, framing and shipping costs really begin to limit those who can participate in photography. As I tell my students, “submission costs are one thing, but god forbid your work gets accepted, that’s when things get expensive”.

In my opinion and experience, I would always put marketing dollars towards portfolio reviews. If I can identify two sources that have helped in my success: one would be from relationships made at review events (with both reviewers and photographers) and the other would be from my relationships with other photographers. Photographer friends have introduced me to their gallerists, reviewers have offered opportunities, sometimes years later. And we forget that our fellow photographers might also become gallerists, editors, writers, and curators and those early relationships mean a lot.

As for juried competitions, they are a good way to get work under the juror’s eyes—the key is to submit to competitions where you are interested in having that juror see your work. I have certainly found photographers to feature from being a juror and even have become close friends with photographers who I have selected for shows after they reached out to me.

Lily in Turquoise, from Revisiting Beauty

SH: You recently told me you hadn’t looked at the film from a photo shoot you’d done a month ago. Tell us about your practice as an artist and your workflow? Do you shoot a lot and then look at it all at once? What is your editing process? Do you feel shooting film has ever limited you or has it given you an advantage? Have you decided to embrace digital or are you still shooting all of your artwork on film?

AS: I shoot whenever there is an opportunity—on a trip, setting up a still life at home, seeing a shaft of light that looks interesting, finding someone in the neighborhood to sit for me. Most of that work is not done for a project, but more for myself and I’m in no hurry to process the film. When I am working on a project, I set aside time and become very focused, trying to create a fair amount of photographs at one sitting. Sometimes it takes me a year to get through all the film, getting it to a place where I want to launch it into the world. I think TIME is an important component to photography, not just in creating the work, but allowing the work to percolate and leaving space for deep consideration. I sometimes think photographers have a tendency to rush projects out.

As for my work flow, I will initially have my film processed and get low-res scans made so I can see what I have. Once I make my edit, I scan my film into larger files and do the usual tweaking in Photoshop—many hours have been spent cleaning negatives! And when I can, I return to the darkroom.

Being a film shooter is a completely different experience to being a digital shooter. One isn’t better than the other, they are just different. I do almost all of my editing in the camera, so am only shooting a handful of frames of each image. Also using a medium format camera makes me slow down which makes the work more formal. I consider the shot before I hit the shutter and then commit to my vision, without being able to see what I have captured. Certainly digital photographers can do this, but most don’t. One of my friends described digital shooting as Spray and Pray. Film shooting is more about the Pray.

The only time I feel at a disadvantage about using film is when something needs to be turned around immediately, but that’s when I might pull out my iphone. People complain about the cost of shooting film. I use a camera from the 1960’s that rarely needs repair, and I limit the amount of shots I take so it actually isn’t as prohibitive as one would think.

For me, there are two important parts to shooting film. One is that I have a tangible photographic legacy—if my scans disappear or my computer crashes, I still have the rolls of film that will continue on. The other is that there is a quality of light and color unique to analog work.

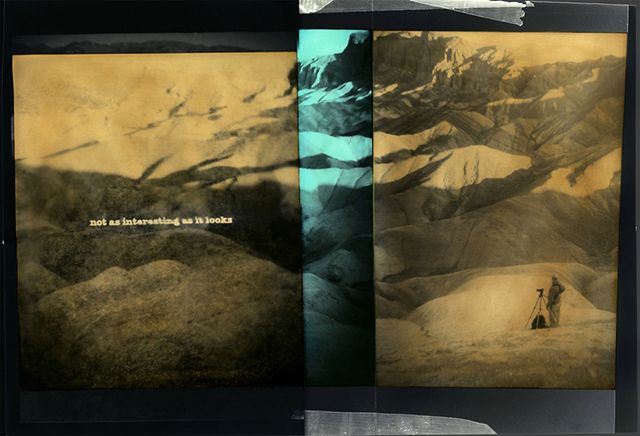

Not as Interesting, from Shadows and Stains

SH: You also talk about rejection very honestly and have said you’ve experienced plenty of it over the years. What kept you going in times when a project wasn’t coming together or finding an audience? Do you have a good example of a project you scrapped entirely after months or years of work or did it just change direction and morph into something else?

AS: I look at every aspect of my photographic journey as a learning experience. Truly there are times that I celebrate not getting into an exhibition as I won’t have to frame and ship the work. I’ve also come to understand that it’s all subjective. When I get rejected, I understand that the juror just might not resonate with my work or that there is work far superior to mine that has been offered up. I have 2 seconds of disappointment and then move on. It’s all part of putting our work out into the world. The key is to believe in your work when it seems no one else does and to learn from your rejections.

As a juror, I have had to let go of work that is often very worthy of wall space, but because I am also creating an exhibition and I have to keep that in mind the audience and the breadth of the show—I can’t show three similar images or something that doesn’t quite fit the theme.

Early in my career, I worked on a project for a year, and then one day, I realized that it didn’t have enough substance to stand the test of time and that ultimately, it was a learning experience for me. The work still has meaning to me, but I have never released it into the world. As for other projects, I am a tough editor of my own work and I can tell pretty quickly if the work is weak or the concept is not working. I have another project that I have continued to shoot for 3-4 years and I still haven’t figured out its heart and soul. I will keep at it, but I’m not worried if it continues to allude me.

SH: Your work is so unusual and yet it all ties together. It is almost always slightly humorous and offbeat, but it is also quite formal and poignant. Where do you think your artistic voice comes from and what do you see as the themes you keep returning to?

AS: Well, I would say that some of those adjectives apply to my own personality. My mother had similar characteristics—she was elegant and formal to the outside world, but at home she had a wicked sense of humor (as did my father) and did lots of quirky things to make our childhood more interesting. I am drawn to very odd things and lean a bit to the dark side –when other people find something creepy, I’m all in. I’ve never found a piece of taxidermy I didn’t love.

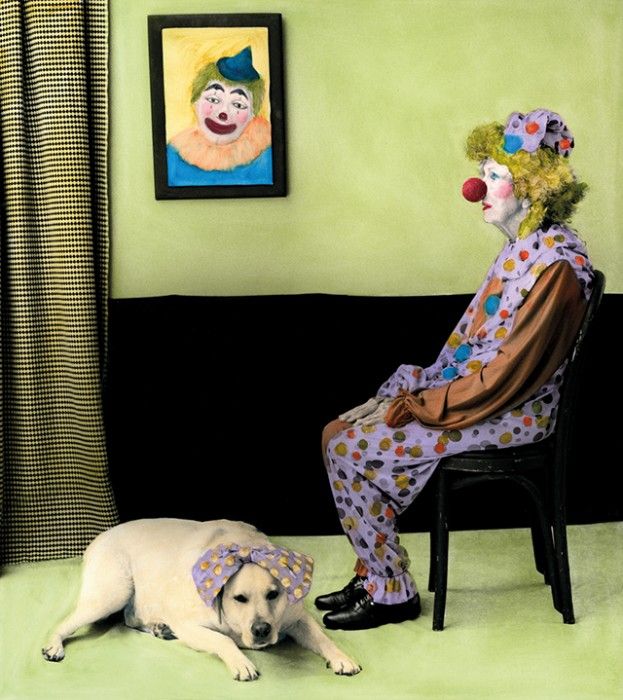

Arrangement in Green and Black #20, Portrait of the Photographer’s Mother

In terms of themes I return to, I think simply the poignancy of being alive continues to draw my interest. I love to analyze what it feels like to be a child, a teenager, an adult, or even a dog or a doll. My particular camera and the square image helps unite my work, and for my color work, my love of things in Technicolor. Almost all of my work is autobiographical, pulling from all the recesses of my life, my interests, and my experiences.

SH: Slowing down and working on a project for 5-10 years seems like a lifetime now, when people are creating new projects each year. What is your personal philosophy on this?

AS: I think it takes at least three years to truly understand and explore a project. Maybe that’s why many MFA programs are two to three years long. Honestly, I would say that I continue make work for many of series I have produced, except for those where it isn’t possible. I am continuing to add to People I Don’t Know, Shadows and Stains, Revisiting Beauty, Spring Fever, Hollywood at Home. Time allows for new considerations and many of my projects may end up being lifetime explorations. And why not?

Hotel Fiorita, from Daughter

SH: You are originally from LA, but I know you lived in NY and started your career there and still have a great love for that city. Your work has many LA themes to it, from the self-portraits in which you “play” different movie characters, your shots at Legoland, Hollywood at Home to your recent glamorous shots of young girls in Revisiting Beauty. Do you think the themes in your work would have been different if you had stayed in NY? Have you a purely NY project you’d like to do?

AS: Interesting question. I have no idea how my photo career would have even happened if I had stayed in New York. There is a good possibility that I may not have become a photographer at all. I might have continued in fashion as an editor or designer. But I am grateful that moving across the country created an opportunity where I could change my focus. I started my photo career in Los Angeles so my focus and inspiration has been on L.A. and California.

I love photographing in New York– I think all photographers want to capture the city in a unique way. I never get tired of making work there. It’s a city that is completely alive at all hours of the night and day and humanity is ever-present. It’s a lot harder to capture Los Angeles in the same way, as it’s a total car culture. I wish I had captured New York when it was dirty and wild and all about drugs, sex, and punk rock.

SH: What is next for you? Any thoughts on future projects or do you know where Lenscratch is going?

AS: With so much going one with the book, I gave myself permission to not feel the pressure to work on a significant project this year. I had no idea that publishing a book would be so all encompassing.

I have been itching to take my photographs in a new direction. I want to get back into the darkroom and expand on what I started with my Shadows and Stains project. I want to get messy and push my photographs into new arenas. I also want to break out my 4×5 and make using it second nature. My Mamiya 7ii and 6 have been waiting for me to use them…so that’s on the to do list too.

As for LENSCRATCH, we launched The States Project this summer where one photographer from each state shares a week of posts of photographers from their state. The result has been fantastic—we are shinning a light on a wide array of image-makers that we might never have found and I think it’s connected the States Editors to their regional community in a more significant way. We still have a long way to go and I’m always excited to see what that week will hold.

We have some very exciting things in the pipeline that I will announce down the line and we have lots of ideas to keep the site interesting. I am hoping to also do monthly posts about the history of photography, featuring interesting photographers from the last 150 years. If any educators would like to contribute to this project, let me know!

If I can go off topic here, I wanted to take this opportunity to celebrate all that YOU do for our community, Sarah. The creation of Filter Photo Festival has been no small feat and your directorship has steered the festival into incredible directions, truly galvanizing the mid west photo world. You are also curating and coordinating amazing opportunities for photographers in Los Angeles and Chicago…and are a wonderful photographer to boot! Bravo and thank you, my friend!

Inquiring Minds, from Paradise

For more of Aline Smithson’s work: Aline Smithson Photography, Lenscratch

To order the book Self & Others: http://alinesmithson.com/books/self-others/

Location: Online Type: Interview

2 responses to “Interview with photographer Aline Smithson”

Leave a Reply

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

[…] will enjoy the interview. >>>>> F-STOP […]

great interview!