blog

“Ralph Eugene Meatyard” by David Cory

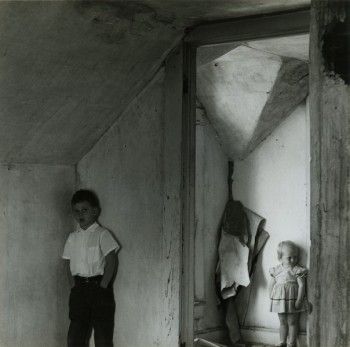

Untitled, 1961. ©Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

When the esteemed editor of F-Stop Magazine suggested writing about a favorite photographer in connection with the publication of my portfolio “Revolution,” I immediately thought of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Since I first learned about him during a portfolio review with Professor Jeff Curto of College of Dupage a few years ago, I have developed an affinity for Meatyard. Like him, I am happily married, I have a day job, and indulge in photography when I can. I enjoy experimenting with photography, and Meatyard certainly did that. I live in northern Indiana, away from the major cultural centers of the coasts, but near a major university (Notre Dame). Meatyard was equally removed from the coasts in eastern Kentucky, but lived near the University of Kentucky. Most of all, I admire his ability to turn the commonplace and even the grotesque into fine art.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925-1972) was an optician in Lexington, Kentucky, who pursued his avocation of photography on weekends. He printed his photographs once a year. He rarely explained his photographs, preferring to let others interpret them. When he died of cancer at age 46, he left behind an impressive body of work that continues to puzzle, challenge, and inspire its viewers.

Had he done nothing more than make eyeglasses, his life might be summarized by a few banal facts—facts common to the lives of many of his generation. Born in Normal, Illinois in 1925, he graduated high school during WWII and served in the navy. He attended college, but didn’t earn a degree. He learned the optician’s trade through apprenticeship. He married after the war, and he and his wife Madelyn contributed three children to the baby boom. He was a Methodist, a small business owner, a PTA president, and the coach of a boys’ baseball team.

But his influence is felt today because there was something uncanny—a term he himself applied to some of his photographs—about Gene Meatyard. When Madelyn gave birth to their first child in 1950, Gene bought a camera to photograph his son. If he had been content with making family snapshots, his legacy might have been limited to a shoebox full of contact prints and bottles of expired chemicals in the makeshift darkroom in a bedroom of the Meatyard home. After he bought his first camera, he joined the Lexington Camera Club, a group more concerned with the art of photography than the technical details of making pictures. Meatyard studied photography under fellow Lexington Camera Club member Van Deren Coke. In 1956, Meatyard and Coke traveled to Indiana University for a photographic workshop run by Henry Holmes Smith. At the Bloomington workshop, Minor White suggested a list of reading materials for serious photographers, including two books about Zen, a philosophy which Meatyard subsequently embraced, and which influenced his photography. His project “Zen Twigs,” featuring tree branches with backgrounds blurred by a shallow depth of field, is the most explicit expression of Zen in his work, but many of his enigmatic photographs could be viewed as visual forms of the Zen koan.

Meatyard shared an interest in Eastern philosophy with his friend, the widely-published Trappist monk Thomas Merton, who lived at the Abbey of Gesthemani not far from Lexington. Meatyard took enough photos of Merton to fill a book titled Father Louie. Besides Merton, Meatyard was friends with many intellectuals. Because of the presence of the University of Kentucky in Lexington, the area was home to or visited by more poets and writers than one might expect.

Meatyard lacked a college degree, but he read avidly on a wide range of subjects. He read about many forms of art, including acting. He applied theatrical concepts to staging tragicomic photos of friends and family. He read philosophy and poetry. Poet Guy Davenport recalled that Meatyard kept on the front seat of his car a copy of William Carlos Williams’ Paterson, which he would read while driving. “This rather scared me if I was in car,” said Davenport. “But he said he could pay attention to driving and read the poem at the same time.”

Meatyard put a good deal of effort into choosing backgrounds, often posing his subjects in or around decaying houses. He also made use of props such as dolls, masks, shards of a broken mirror, an ice pick, and a pickaxe. His final project resulted in the posthumously published book The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater. In this project, Madelyn Meatyard wore a rubber hag’s mask, posing with friends and family members who wore the mask of an elderly male. In the first image of the book, Gene is the old man and Madelyn is the hag. In the final image, they have reversed roles by exchanging masks and clothes. Gene Meatyard originally conceived of the book as a replica of a typical family photo album of the early-to-mid twentieth century, with 7×7 inch prints on black pages and captions handwritten in white ink. His vision was not carried out in the first edition, but James Rhems’ more recent The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater and Other Figurative Photographs presents the photos as Meatyard intended. By concealing the faces of his subjects with masks and naming everyone Lucybelle Crater in the captions, Meatyard forces us to reflect on the nature of individuality and identity. He also used the masks to call attention to something deeper. He wrote to Jonathan Williams, publisher of the the original edition of The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, “Billboards in any art are the first things that one sees—the masks might be interpreted as billboards. Once you get past the billboard then you can see into the past (forest, etc.), the present, & the future. I feel that because of the ‘strange’ that more attention is paid to backgrounds & that has been the essence of my photography forever.”

His photography was not limited to posed tableaux as in Lucybelle. Meatyard collaborated with his friend Wendell Berry on the book The Unforeseen Wilderness: Kentucky’s Red River Gorge. Meatyard’s dark, powerful landscapes and Berry’s text were protests against the proposed damming of the Red River by the Army Corps of Engineers, an event which fortunately never occurred.

Motion was an important element of Meatyard’s art. The faces of his subjects might be blurred as they shook their heads, their arms might be obscured by waving, or their entire bodies might acquire an ethereal quality as they walked or jumped during the exposure. I can’t hope to describe Meatyard’s “Motion-Sound” series of photos any better than Judith Keller did in her book Ralph Eugene Meatyard:

Meatyard searched continually for a non-objective art that would be wordless poetry, spontaneous music without sound. The ‘Motion-Sound’ pictures of his later years brought Meatyard’s passion for music and, paradoxically, the silence of Zen Buddhism together in photography. In creating the series, he focused the camera on a natural scene (or one containing plain rural architecture) and then moved it slightly. The result of this action is an image that suggests sound while abstracting natural forms. The landscapes of the ‘Motion-Sound’ series are in stark contrast to the evocative, more traditional views of the Red River Gorge that Meatyard was executing during the same years.

Meatyard experimented with even more abstraction with his “No Focus” photos. By opening the shutter without focusing, Meatyard produced images freed from the conventions of traditional photography.

The two sides of Meatyard—the quotidian and the fantastical—persisted beyond his death. In the 1974 Aperture monograph dedicated to Meatyard, Guy Davenport wrote about the two funerals held for Meatyard in 1972. The first was a Protestant ceremony that Davenport described as “thoroughly dull,” and one that Gene would not have wanted to attend. The second, “made up out of the family fund of inventiveness,” involved a small group of family and friends drinking wine made by Gene and spreading his ashes in a remote area of the Red River Gorge that he loved so well. Followed by a sumptuous picnic lunch in the woods, this was the funeral the departed would have wanted to attend. RIP, REM.

Links to Meatyard photos at:

PDN Photo of the Day

Fraenkel Gallery

George Eastman House

Links to musings about Meatyard:

Jeff Curto’s Camera Position Podcast about Ralph Eugene Meatyard

“Behind the Billboard, or Lucybelle Unmasked” by James Rhem

Location: Online Type: Essay, Featured Photographer

One response to ““Ralph Eugene Meatyard” by David Cory”

Leave a Reply

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

[…] You can read the full article here […]