blog

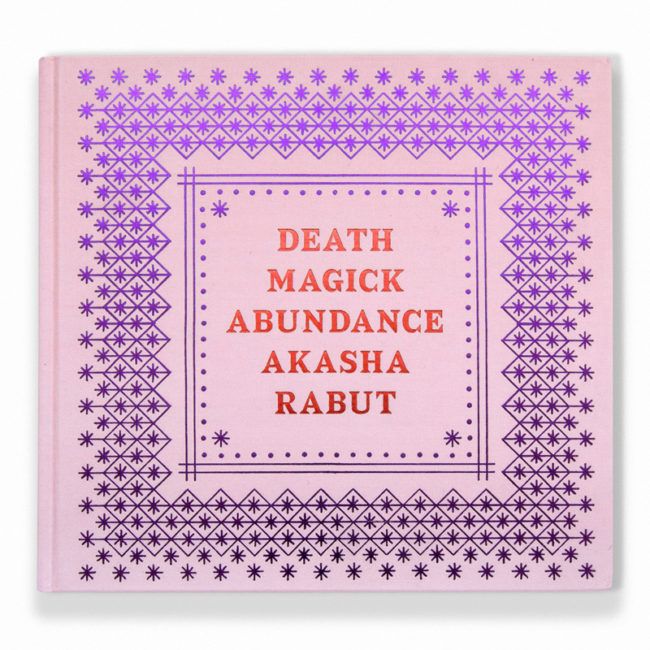

Book review: Death Magick Abundance by Akasha Rabut

Death Magick Abundance, the first photo book by New Orleans photographer Akasha Rabut, is the culmination of her nearly ten-year collaboration with the people of New Orleans who invited her into their lives to photograph them. Her images celebrate the city’s thriving culture through the pink smoke of the Caramel Curves, the first all-female black motorcycle club; the Southern Riderz, urban cowboys on horseback in the city streets; the second lines’ exuberant fashion, music and style; and life that seems to spring from dilapidated corners.

Rabut writes, “Witnessing how the people of New Orleans adorn themselves in a dizzying array of hallucinatory fashion, observing how music and style disseminate from the streets instead of from a supposed elite influencer class, and cultivating friendships with the people who comprise the heart of this book — these experiences have forever changed my life.”

The title echoes the spirit of the second line parades, a tradition sprung from funerals that is central to the social lives of many New Orleanians. In his essay in the book, New Orleans photographer Sam Feather notes, “Second lines are a source of power. In a city where so much is oriented toward outsiders, the parade is not for sale, not advertised, not sponsored by corporations, not accompanied by souvenirs. Despite very tight budgets, you will see some of the most creative dressing in the world at the second line. It’s a stage and a dance club and a neighborhood block party all walking by in the afternoon. It’s a tiny economy.”

More than any party, parade, team, or disaster, New Orleans is defined by the people. For nearly a decade, she has documented this thriving culture. Seeking to interpret and preserve a sacred cultural heritage while redefining itself against a constantly shifting landscape, this book is a conduit for the love and unending beauty of New Orleans and its people to flow to the rest of the world.

The Caramel Curves and Southern Riderz featured prominently in the book are largely BIPOC groups who invited Rabut to their meetings, their streets, and their homes. In articles from Dazed Magazine, and Postscript in 2018 Rabut talks about her closeness and relationships with her subjects. Yet she doubts herself by wondering why she is the person telling these stories, because she’s not from there despite the fact she has spent years photographing them; she’s a transplant. “I will say being a woman was really what helped forge the connection between myself and these groups,” Rabut says. “It’s often white men who get this kind of work published and out into the world, but what sets my photography apart is its intimacy and tenderness. And I think because of my openness and curiosity as a photographer and woman of color, I often attract this sense of comfort in my subjects. I’ll ask someone off the street if I can take their photo and the next thing I know I’m being introduced to their family or walking through their home.”

Rabut’s subjects genuinely connect with her lens. Scenes feel genuine, and Rabut has a gifted eye for light and composition and selecting the right environment to set the stage to showcase her subjects. All strengths of the work considered, which there are many, I couldn’t help but feel a pull in the opposite direction as well. I see work which draws in the viewer, and I see work which feels like the depiction on an object within a space. I picked up on a perceived distance in her images. Not all of them, but enough of them to notice a pattern. Rabut is definitely close to the people she is photographing, she spends years with these groups, she lives in the community, yet there is a perceptible extra few feet of emotional and physical distance in some of her images. Maybe the famously insular city and residents of New Orleans will always be just beyond the reach of the lens.

Maybe not.

I was talking about Rabut’s work with my wife, and the discussion soon turned to how a viewer ‘reads’ the images. I feel these questions should be considered when considering the book against reading the supporting text: What does the extra space in the frame around a figure say about the subject? What does it say about the involvement of the photographer? Why crop a person at the knees in one scene, versus showing the entire figure in another? If an image concentrates on the subject more, if the crop in camera is a bit closer, what does that say about the image and the entire body of work if we apply the same question? Does the project, or body of work, become a story of individuals, or does it tell the story of a place which features individuals shown in context? Does it matter if we see a black woman wearing a bucket hat and patterned leggings is holding a Stacy Abrams political sign in front of a metal clad pole barn, or would the viewer get more or less information if Rabut chose to take two steps closer to that woman? What does that decision do to the narrative? What if the viewer focused on the lines in her face, her expression, the way she carries herself, versus the scene she is in? So much of photographic critique involves debating and defending the path not taken – so I include this narrative because it was part of my process reading the images Rabut puts forth in her book, and in her projects.

Without critical thinking, viewers of art and images are passive; not actively engaged. I believe too many people writing about photography and photo books are passive, or afraid to challenge work and ask questions for valid reasons, or raise critical points. I’ve been guilty of it myself. That said, I don’t want my opinions to take away from the many strengths of Death Magick Abundance, nor the New Orleans Renaissance after the Hurricane Katrina and the socio-economic plight which surely will linger for decades, if not generations. This is a story worth telling; this is a story of defeating overwhelming odds, endurance, and personal expression.

Ultimately Death Magick Abundance refers to the cycle of life. This book is about death and life; it’s about magical New Orleans and the people who rebuilt it after Hurricane Katrina. People who believe in something worth fighting for. Rabut is also fighting the good fight, and giving back to the community she has adopted. It’s all about balance between the good times and the bad; Yin and Yang, and the infinite loop of birth, life, death and rebirth… Like a burnout on the pavement of life.

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

© Akasha Rabut from Death Magick Abundance published by Anthology Editions

Death Magick Abundance

by Akasha Rabut

with contributions by Sam Feather and Anne Gisleson

10.6 inches x 10 inches

216 pages, 169 images

Akasha Rabut is a photographer and educator based in New Orleans. Her work explores multi-cultural phenomena and tradition rooted in the American South. Akasha is also the founder of Creative Council, a mentoring program for young people in New Orleans pursuing careers in the arts. Akasha’s photographs have appeared in museums and galleries around the world. She holds a BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute.

Anthology Editions uncovers and fashions cultural narratives as books, music collections, online experiences, and exhibitions. Stories of every caliber and color communicate and resonate within the new canon Anthology Editions seeks to establish. For more information, visit: https://anthology.net/books/.

Location: Online Type: Book Review, Portraits

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply