blog

Interview with photographer Marcus Xavier Chormicle

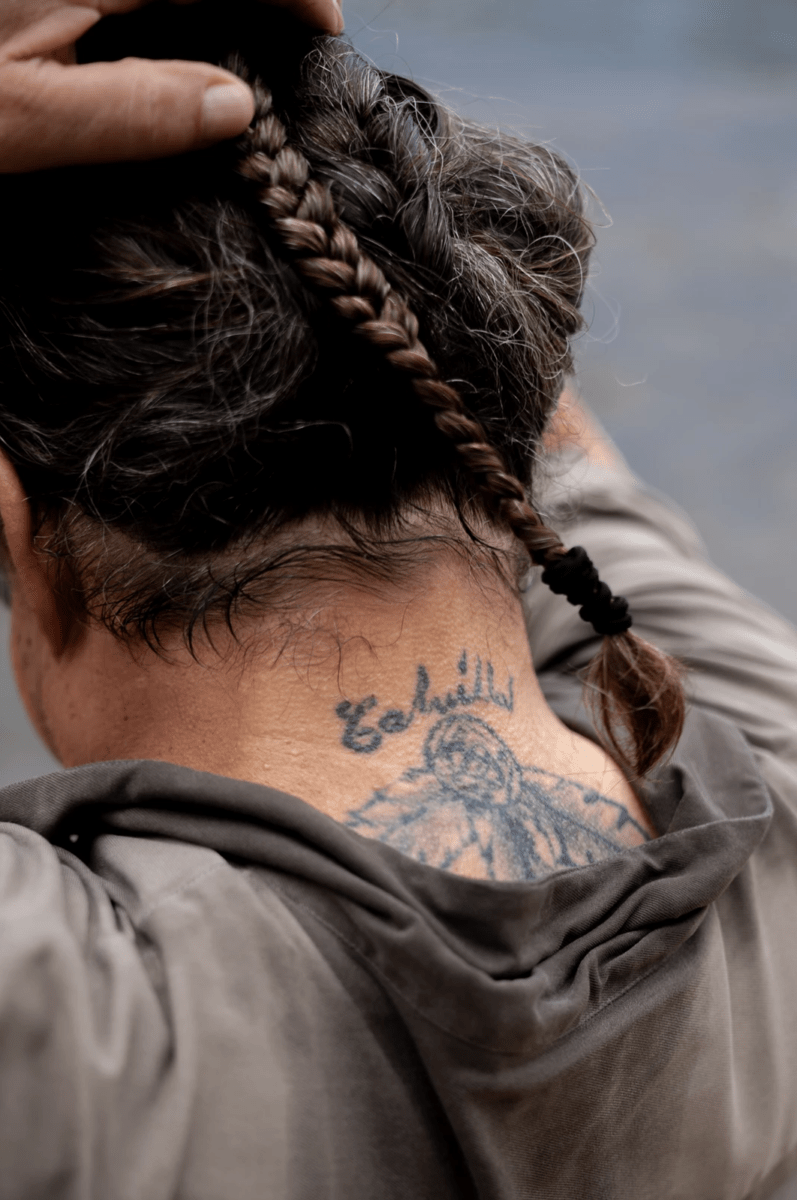

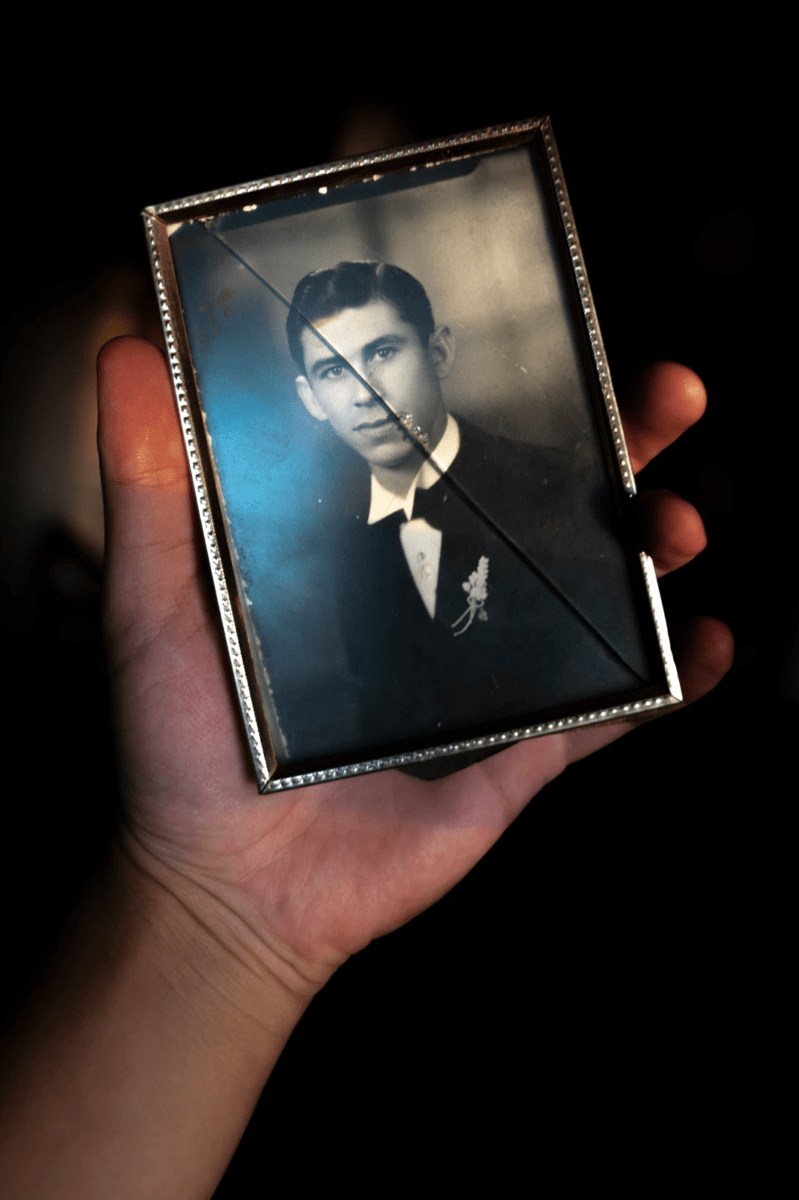

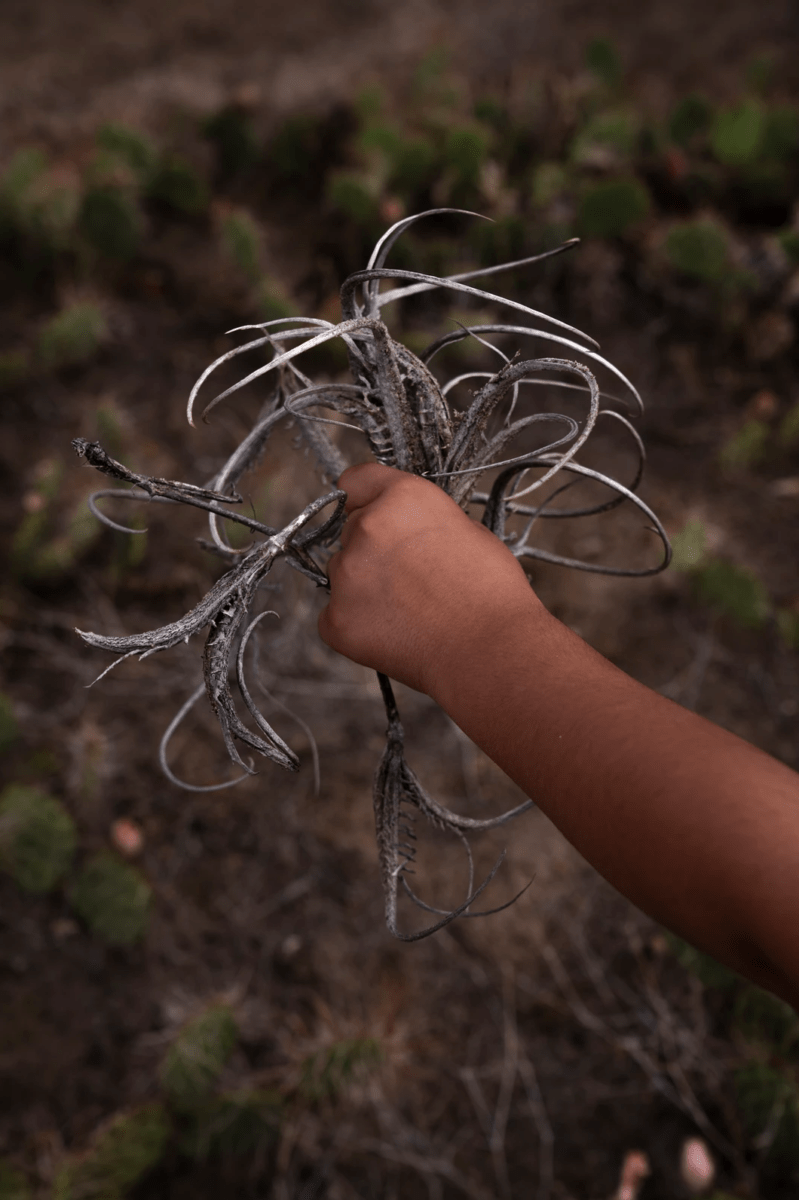

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

Marcus Xavier Chormicle is one of our featured artists in the Portfolio Issue 2020 #104. The work from his project, Still Playing with Fire, is a photographic series made in Las Cruces, New Mexico, his hometown, which interrogates the violent history of the region and the effects this history has on the people still living there today. I had the opportunity to interview Marcus on this project and his work for this issue.

Cary Benbow (CB): Who are the people that appear in your photographs? Are they more important than just being a figure in the frame?

Marcus Xavier Chormicle (MXC): For this project, nearly everyone is family, and everyone is part of my community. They’re the most important people in my life, so their value lives far beyond any image I could make. I feel that way about anyone, but especially my family and my community. They created me, so I approach my work and myself as not just a representation, but a reflection of them.

CB: Why did you decide to pursue photography?

MXC: I had always been obsessed with memory and how my family recorded our communal memory through family photos. I would spend hours looking at those photos, and listening to the stories that accompanied them. I had always felt compelled to create similar work. When I had the opportunity to go to college I wanted to pursue photography, and ultimately decided that it was the one thing that really brought me joy, which left me no choice but to follow that path.

CB: That said, what was your start into photography?

MXC: My start in photography goes all the way back to looking at family photos with my mother and grandmother. I think that was a formative experience for how I viewed the world and my family, as well as how I interacted with them. From there I would beg to use my grandmother’s camera at family parties and gatherings to photograph my cousins and our dogs. That’s when I was very little and throughout the rest of my life I wanted to chase that. When I was 16 my father and grandma pitched in to get me a beginner digital camera; that’s when I first really felt like a photographer.

CB: What else do you like about it – why make photography your choice of expression?

MXC: What I like about photography, versus any other medium of expression, is that you’re actively and openly interpreting a singular perspective. With mediums like painting or sculpture, you create something from nothing, from a lump of clay or onto a blank canvas, which is what makes those mediums exciting to me, the creation. But with photography, you’re creating something unique from the world as it already exists. You’re taking the light from 1/250 of a second, and making a statement that this particular fraction of a second is worth looking at. That the person, place or thing is worth looking at, and that the moment deserves to be thought about for a longer time than it actually existed in front of you.

CB: Why do you photograph, or what compels you to make the images you create?

MXC: It provides me a way to interact with the world in a unique way. Through photography I am able to explore emotion, memory and perspective while engaging with my surroundings. I am compelled to make my work so I can help assert the artistic and cultural value of the people and places around me. Photography is a means to project an internal world on to the external, and it’s an easy way to convince people to engage with it.

CB: Why did you choose a quasi-documentary style for the work in your ‘Still Playing with Fire’ project?

MXC: When I went to college I studied journalism, but I quickly found out that I really didn’t buy into photojournalism, or the idea of what much of documentary photography represented. I worked as a photojournalist for a few years while in school, and I love photographing people, even people that are very different from me, but I hate the idea of representing someone’s image if it’s in the service of someone else. Not that work needs to be activism, because I think most of us photographers who feel that way about our work are just kidding themselves, but I wanted to make work that was first and foremost for the people in it, and for myself in a way that was honest. I decided to return to the roots of my fascination with photography and photograph my family. Documentary style is what I was attracted to, and how I had been trained, I also felt it was a complimentary style in which to approach my family, to create space for interpretation in a setting that felt comfortable and certain to me.

CB: You write on your website that your work is about the intersection of class, race and history – can you comment on how you depict these elements in the way you do?

MXC: ”Still Playing with Fire” is about understanding and processing the generational trauma passed down within my family. It’s about trying to make sense of events and feelings that have recurred again and again in my family. So much of our lives are determined before we even step into them by the circumstances around, for better and for worse. Understanding how class, race and history define our lives and how we’ve been taught to relate to each other has been key to me for figuring out how to move forward, how to get better as an individual and hopefully as a family and community.

CB: What work are you currently working on? Any new projects?

MXC: Currently I’m working on exhibiting “Still Playing with Fire” and trying to maintain community art in Las Cruces. I’m establishing a gallery in memory of my late cousin Cristian Anthony Vallejo in Las Cruces, and working with the artist Saba to grow the Picacho Arts district. As far as photo, I don’t currently have a new direction as far as a project, but I think that will find me when I’m ready anyways.

CB: Where do you draw inspiration, or who are your photographic inspirations?

MXC: I try to look at as much work as possible, some favorites I’ve already mentioned, Rivas, Lange and Parks. Other essential photographers for me include Sam Contis, Carlos Louise Bernal, Wendy Red Star, Guadalupe Rosales, Laura Augillar and my friends Juan Brenner and Daniel Ramos. I’ve been lucky to be mentored by people like Liz Cohen, Mark Klett and Benjamin Timpson who’ve contributed a lot to how I approach photography. People such as Elle Pérez, Dawoud Bey and John Edmonds have all been thought leaders for me as far as how I approach the sitters in my work, it’s from reading about them that I came to conclusions about the power of photography to assert artistic and cultural value to the subject. Beyond photography, Fritz Scholder, the Latin Playboys and Star Wars have probably been some of the greatest influencers on me.

I hope my work fits in with these influences; I think everyone I listed has impressed something important on me, and I try to fuse elements of everything I’ve taken away from them into my work.

CB: In a related style of photographic work or style, what do you feel are the obligations of a photographer covering human rights issues? Do you feel this theme is related to your project?

MXC: I used to love advocacy projects, but I’ve really fallen out of that love with most of them. I think Dorothea Lange and Gordon Parks are two of the only photographer’s whose human rights projects I still enjoy looking at, not to say that I don’t take issue with some of the images, I think Parks’ work in Brazil is one of the most significant projects in that vein, it’s powerful, moving, beautifully made and full of decisions I would like to avoid in my own work. I think a lot of it comes down to audience. I don’t want to make a life of sending photos back from Brazil to be looked at by Americans, or really vice versa. Josué Rivas’ work at Standing Rock is probably my favorite contemporary work on a human rights topic, his book “Standing Strong” is incredible, I bought it twice, once more myself and once for my uncle. That project is important, an outsider could look at it and see that, but it was made to celebrate and hold space for the people who were there defending the land and their family, and I think the images in that project must be the most significant to the people who were there, who actually felt the emotions that viewers of the work, like myself, who weren’t there, could only imagine.

As far as my own work, I do believe that it could have cultural or emotional value to others, people who grew up like me, near me, or who have similar life experiences to me or the family in photos, but I try to start with acknowledging that the work is first from my singular perspective and second for the benefit of my family, by creating a record, holding space for them, and hopefully as a means of asserting their experiences as important and worthy of being seen for more than 1/250 of a second.

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

From ‘Still Playing with Fire’ © Marcus Xavier Chormicle

Marcus Xavier Chormicle is a lens based artist from what is currently the Southwestern region of the USA. His work focuses on family, memory and the intersection of class, race and history in the Southwest. He recently returned home to Las Cruces, New Mexico to work as an artist and focus on community engagement and education and currently works with the Picacho Arts District, a community driven arts institution which focus on uplifting and empower the people of Las Cruces, as well as the New Mexico State University Art Museum as a digital marketing specialist with a focus on bringing community groups that have not typically been included in institutional settings within the art world.

In 2020 he founded the Cristian Anthony Vallejo Memorial Gallery at the Garcia Building in Las Cruces. Dedicated to his younger late cousin, the gallery aims to create a space for artists whose work drives cultural and communal conversation that goes beyond art for-the-sake-of-art to generate real change on a communal level. Beginning in 2021 the CAV Gallery will hold exhibitions and host artists, as part of the Barrio Mezquite Artist Residency Program, which focuses on providing emerging artists with work space and the means to create professional level marketing materials to promote their practice.

Location: Online Type: Featured Photographer, Interview

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply