blog

Interview with photographer Rasha Al Jundi

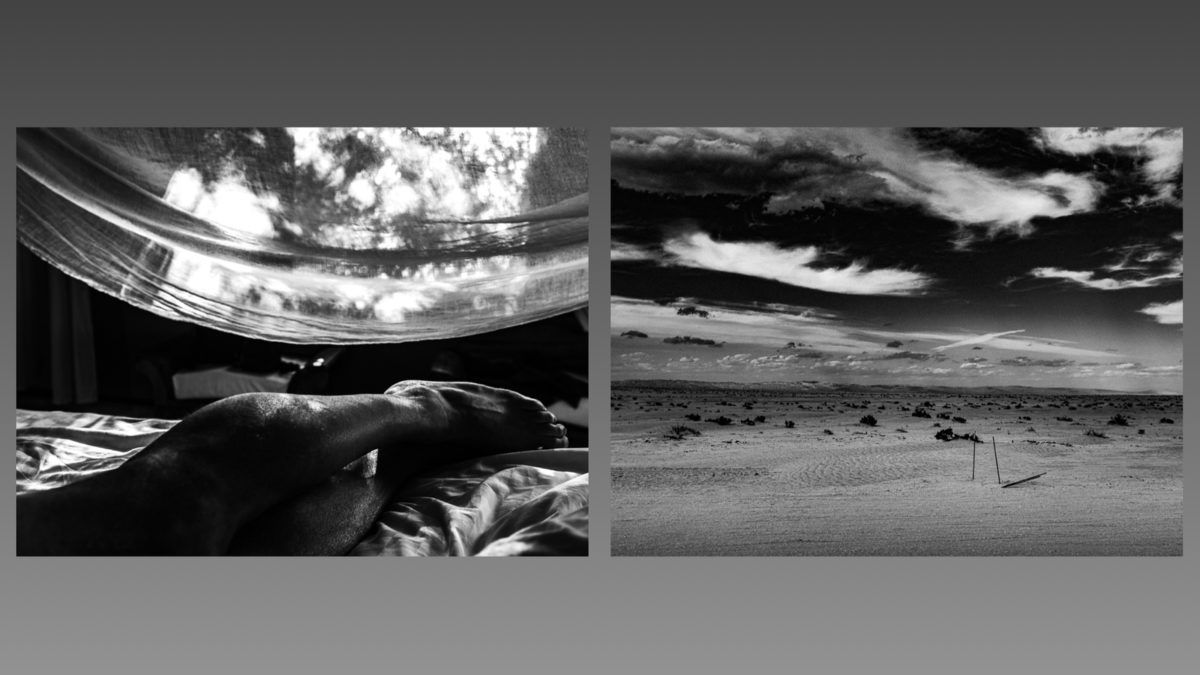

From Red Soil © Rasha Al Jundi

No matter how many gagillion images I’ve seen, within the thousands of that I’ve really seen, sometimes I get blindsided by a photographer’s work and realize I’m witnessing something really worth slowing down, absorbing, questioning and asking about. Fortunately I was able to ask Rasha Al Jundi about her portfolio of work for Issue 116. Her photographic work transcends genres, class, nationality and borders. My rural abode is over 8,000 miles away from Kenya, but I recognize struggle when I see it. I see strength when I see it. And I also recognize when a photographer is passionate about their work.

Cary Benbow (CB): Can you tell us about yourself – how did growing up in Lebanon, and working in the middle east and Africa influence or inform your decision to be a photographer?

Rasha Al Jundi (RAJ): I actually grew up in the UAE and left that to Lebanon for university, but ended up staying and working there for a total of seven years. When I decided to work with communities, on public health issues initially, I ended up in some of the most underprivileged and interesting places in Lebanon where there was a treasure of hidden stories to be told. Now, working in the development/humanitarian sector always involves a level of documentation or storytelling about implemented project, especially to share reports with donors – and make the reports less dry or detached, and more reflective of the human condition on the ground. So, documenting people’s stories was a natural day-to-day activity even if it wasn’t my core job. I think that’s when I realized I had to always have a camera on me to document what I’m seeing in the different places where I’ve lived and worked.

CB: You recently graduated from ICP’s Documentary and Visual Photojournalism program – please talk about your experience at ICP and how it helped your project.

RAJ: ICP was a major catalyst to initiating, guiding and shaping this project. Although I completed the online program, I had the full support and availability of mentors and tutors throughout the project of executing “Red Soil”. I literally moved myself and my life to another part of Kenya for 2.5 months and pushed myself to make images throughout the week for a weekly edit and review in class. I think it’s safe to say that anyone who joins ICP’c DOC program has a solid technical base in photography, and although that was strengthened with additional skills and knowledge, it wasn’t my main takeaway. The main aspects of learning at ICP that helped the project tremendously were learning how to read images, construct a story (or different stories) during the edit and think in a non-linear manner when producing a visual narrative.

CB: Do you feel your work fits into the category of ‘journalism’ rather than ‘creative’ – do you care about labels or categories for photography?

RAJ: I think this particular project can be edited in many different ways that can fall under any label in photography. I can share an edit with more poetic/creative/metaphoric and artistic images only or share more real life day to day “this is what is happening to these people” sort of edit. I guess I don’t really care about categories when it is something I’m working on independent of a certain requirement from a magazine or editor. In general, despite my fast approach to many things in life, I do lean more towards the slow paced method of documentary practice, which I find more reflective, as opposed to journalism. But yeah, photography is such a fluid and subjective medium that labels shouldn’t be used to restrict anyone’s creativity in one way or another.

CB: Beyond your project statement, will you talk more about why you decided to work on the “Red Soil” project? Why is it important? Who is your intended audience?

RAJ: Being Palestinian, with a half-Bedouin background, I can relate to many aspects of the Maasai semi-nomadic lifestyle and why land grabs/loss of land is vital for their survival as individuals, communities and as a culture. I think it is important to related to audiences from contexts that were never colonized or faced significant land losses that were never returned, that dissecting indigenous people’s lands into small parcels and pushing them into cantons is dangerous to leading a dignified life on earth. This basically means a stable home, family and income. It also means having the freedom to practice culture and traditions or beliefs. Those are all basic human rights actually. Now, land grabs have a massive destructive effect on all those basic rights of indigenous peoples. Lands don’t only mean a source of food and water for their animals. Lands are also a very important link to people’s history, culture and traditions (example from Red Soil: the Maasai believe in the spiritual importance of a certain tree called “Orititi”. They pray at its sight and slaughter for certain occasions. They also have certain practices that relate to river beds, hills and grass).

Similarly, Palestinian women historically, since the Canaanite period, derived traditional embroidery patterns that are popular on peasants’ clothes (and are currently being integrated in modern fashion) from natural elements of the land: grape trees, cypress, birds, stars, waves etc.

I believe those values and traditional practices that are related to physical lands are not entirely understood in more developed and industrialized parts of Europe, North America and parts of the Middle East. There tends to be a simplistic and superficial view of how indigenous communities relate to their ancestral lands. It is more complex than just having a parcel of land to cultivate or graze on. This is why I wanted to working on this project and my intended audience is really everyone! Those coming from historically colonial nations; those living in big industrialized and consumer based cities and local Kenyans who don’t understand the Maasai, or other pastoral communities’ way of life.

From Red Soil © Rasha Al Jundi

From Red Soil © Rasha Al Jundi

CB: What/who are your photography inspirations – and why?

RAJ: I really love to look at the work of Cuban photographer Raul Canibano. His documentation of daily life within his community is so out of the box and like him (I met him personally), I use a fixed lens which forces me to get close and take chances. Eugene Smith is definitely a historical influence and inspiration for his body of work that moves me to tears (a good sign) every time I look at it. Kodelka is a master in making still life come to life! Beyond his work in the European continent, (Kodelka’s) work around the separation wall in the occupied West Bank is extremely moving. Among women photographers, I really love Thana Faroq’s work: a Yemeni photographer based in the Netherlands who works on issues of forced migration and women (“I don’t recognize me in the shadows” is sublime). And I have to mention my ICP peer Taniya Sarkar from West Bengal, India for her amazing and passionate work on inter-communal violence and its connection to the history of colonization and the partition. Her work is very inspiring.

From A State of Mind © Rasha Al Jundi

CB: How do you describe your photography to someone who’s not familiar with it?

RAJ: I would say I lean towards documenting social issues that are with us today due to colonial history/ongoing legacy that we didn’t or are not dealing with correctly, so never really resolved. I like to get close to people and really get to know them. When working independently, I choose stories that move me, which I can relate to. That also includes sharing people’s happiness not just sadness (it’s not all doom and gloom!). I follow my passion and that’s when I work really well.

CB: Has it been difficult to start and stop working on projects that involve people in need?

Not necessarily, no. Many stories have a social “concerned” aspect to them even if this doesn’t show from the initial “look of things”. For example, I’m currently working on a personal project documenting individual stories of Palestinians in exile. One can say that many have stable and generally good lives where they live at the moment. However, once you start asking questions, you realize that many are in fact stateless and are unable to move freely. Others are dealing with PTSD which doesn’t really show but comes out when the right questions are asked. And again, others live in constant fear of losing a job or an academic prospect because of their political views so are forced into silence which impacts them in different ways. On the other hand, if a Maasai household is able to retain more than a 100 cows a season (rare these days due to drought as well as limited land), they are a wealthy household even if someone like me, an outsider, views their simple homestead as a sign of poverty. In fact, they are not poor or needy at all. We tend to perceive someone in a certain way and put them in the “people in need” box while they fit in an entirely different category. My point is, there is always a story for “concerned” photography if one looks beyond the “front stage” facade that we all wear, present or perceive of others.

CB: If any of the work in the Red Soil project was taken before or during the pandemic, does the COVID-19 pandemic change the way you view these images?

RAJ: I don’t think so actually. But I’m also not sure as I started this when many rules were beginning to relax in Kenya. I can say that I focused on remote and rural communities/locations which were hardly if ever impacted by COVID due to the remoteness and people’s extremely limited trips to larger towns or cities (I asked if anyone got it and the answer in three different locations was no). I guess the only impact COVID-19 had was the absence of tourists for some time, which might have changed the narrative if I had made this story during the pandemic: I question land grabs for “conservancies” that mainly attract exclusive tourism and bring in significant income to the government and a few large-scale ranch or conservancy owners, while pushing indigenous communities out or involving them in a very limited and unequal manner. This might have been different in the absence of tourism during the pandemic.

From Red Soil © Rasha Al Jundi

From Red Soil © Rasha Al Jundi

CB: How do you decide to take on new projects? For example: do you work on assignments for news agencies, or are you solely independent?

RAJ: At the moment, I am independent. I am on the look out for assignments for sure: definitely for income purposes but also because they lead to exploring new contexts and stories. It is always a way to learn more about the world! I’m currently researching a third chapter for Red Soil as I received the inaugural Tom Stoddart award from Ian Parry Scholarship for it.

From Dianis Changing Waters © Rasha Al Jundi

From Dianis Changing Waters © Rasha Al Jundi

CB: Do you keep a journal, keep notes or write about the places and people you see? If so, would you share a meaningful entry?

RAJ: I occasionally do and record thoughts as well when I don’t have a pen/notebook nearby. A few months ago, I was watching a documentary film in Nairobi about the Palestinian catastophe in 1948 (or what we call “Nakba”), and an old woman who lived through it recalls the events in her village with this opening line “When the grapes were sour…”.

I took out my notebook and in it I wrote (translated from Arabic):

“When the grapes were sour..” – look at how our people related to the land. The seasons remind them of the start of historical events. What a symbol of our traditional connection to a physical form. I will never forget this phrase.

(This inspired the title of my ongoing project “Sour Grapes: Emboirdered Palestinian Stories from the Exile” and I used the same Arabic quote for that version of the title)

(Editors Note: See Rasha’s project here: https://www.photographerswithoutborders.org/online-magazine/sour grapes )

::

Rasha Al Jundi is a Palestinian documentary photography and visual storyteller. Between 2009 and 2021, Rasha worked with several local and international civil society and non-governmental organisations as a program manager in the Middle East, and in north and sub-Saharan Africa. Her work generally follows a social documentary pathway. She aims to focus on decolonizing oversimplified narratives around historical injustices and their contemporary impact on individuals and marginalised groups. Rasha is a 2022 graduate from the Documentary and Visual Photojournalism program at the International Center for Photography (ICP). She is currently based between Berlin, Germany and Nairobi, Kenya.

Location: Online Type: Black and White, Documentary, Featured Photographer, Interview

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply