blog

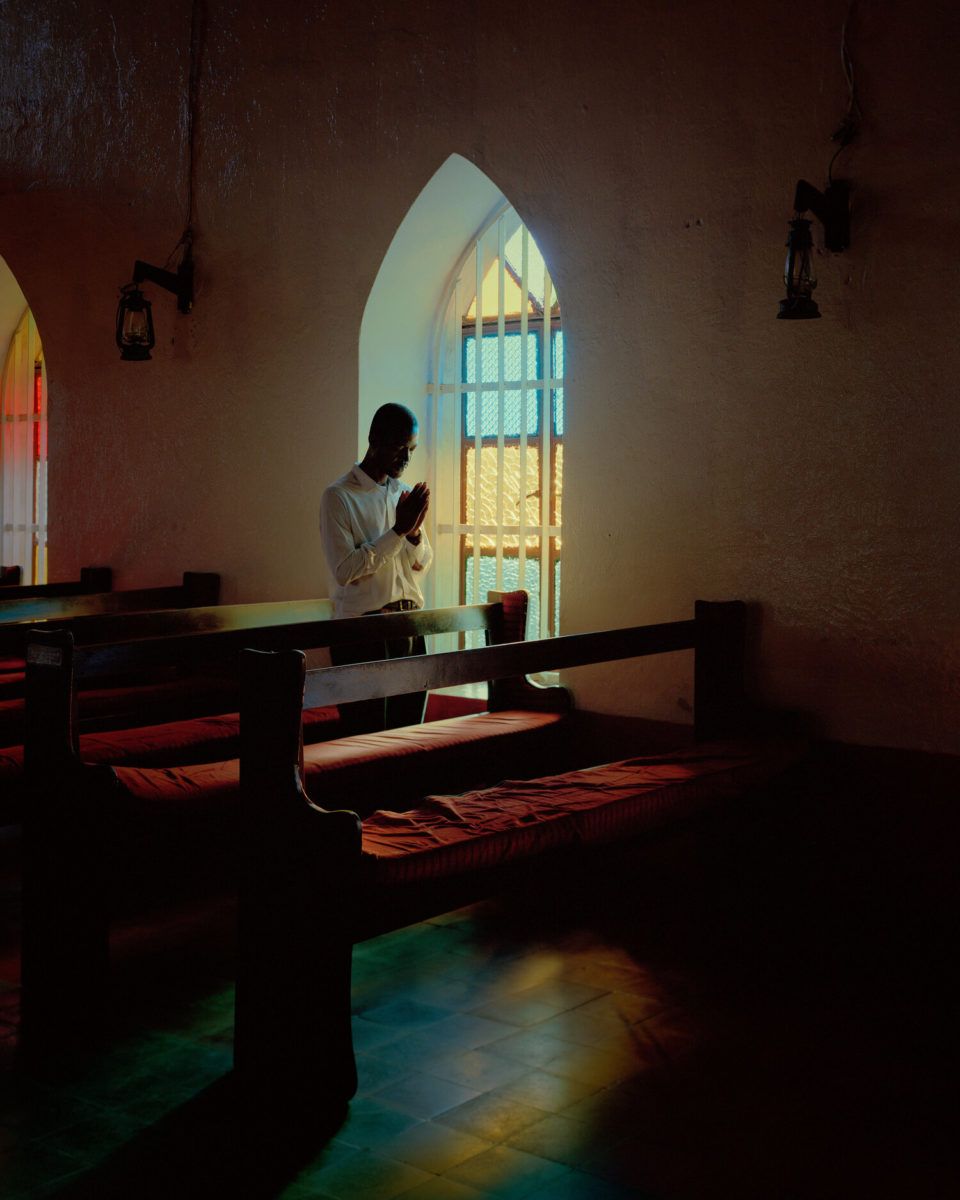

Reaching for Dawn by Elliott Verdier

Samuel, in a lake nicknamed ‘Zwedru Sea’. Zwedru, Liberia © Elliott Verdier

Liberia’s population generally does not speak of the bloody civil war which took place from 1989-2003. No proper memorial has been built, no day is dedicated to the commemoration of the brutal conflict. The country largely refuses to officially condemn its perpetrators, which hinders the collective healing process, and possibility of social recognition of the massacres. Over 250,000 people were killed. Children were conscripted into armies, and crimes against humanity were undoubtedly committed. A collective feeling of abandonment and resignation fills the void left by the government’s inaction, which has led to a new generation of Liberians with uncertain futures, and scarce ability to reconcile their pasts. Reaching for Dawn by Elliott Verdier is a photo book which highlights the struggles of Liberians and the types of futures they face.

Many Americans are unaware of the complicated and problematic history of Liberia. In 1816 the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded by white Americans to encourage newly emancipated slaves and freeborn people of color in America to migrate to West Africa. Abolitionists and the African-American community – many who had already lived in America for generations – were overwhelmingly opposed to the ACS. This backward colonization attempt gave rise to a type of society in Liberia (officially declared a new nation in 1847) which sadly and ironically eventually led to racial oppression much like what transpired previously in America. Over a century and a half later, the tensions (amplified by ethnic divisions, corruption, and economic disparities) inevitably escalated, leading to a civil war. Complicated and problematic indeed.

Elliott Verdier is a French photographer who concentrates on themes such as memory, generational transmission and resilience. He has previously worked on a long-term project and created a photo book focusing on the people of Kyrgyzstan – A Shaded Path. His recent project and photo book about the people of Liberia, Reaching for Dawn, offers three interwoven narratives; one in black & white images, another in color, and parallel to the photographs his digital project includes recordings of men and women recounting their life stories. Verdier’s empathetic portraits evoke the stillness of the surrounding environments, which in turn are echoed in the stillness of the expressions on the faces of the people who appear in the book. The color portraits are direct and honest, and perhaps highlight the complicated history many Liberians carry with them every day. These powerfully metaphoric reflections present a stark contrast to the chaos and suffering people endured. I am struck by the tranquility and stillness in Verdier’s images, especially in contrast to the graphic, and often brutal violence which took place during the war. Passages shared by people interviewed for the project remind us of the harsh atrocities humans will inflict upon one another.

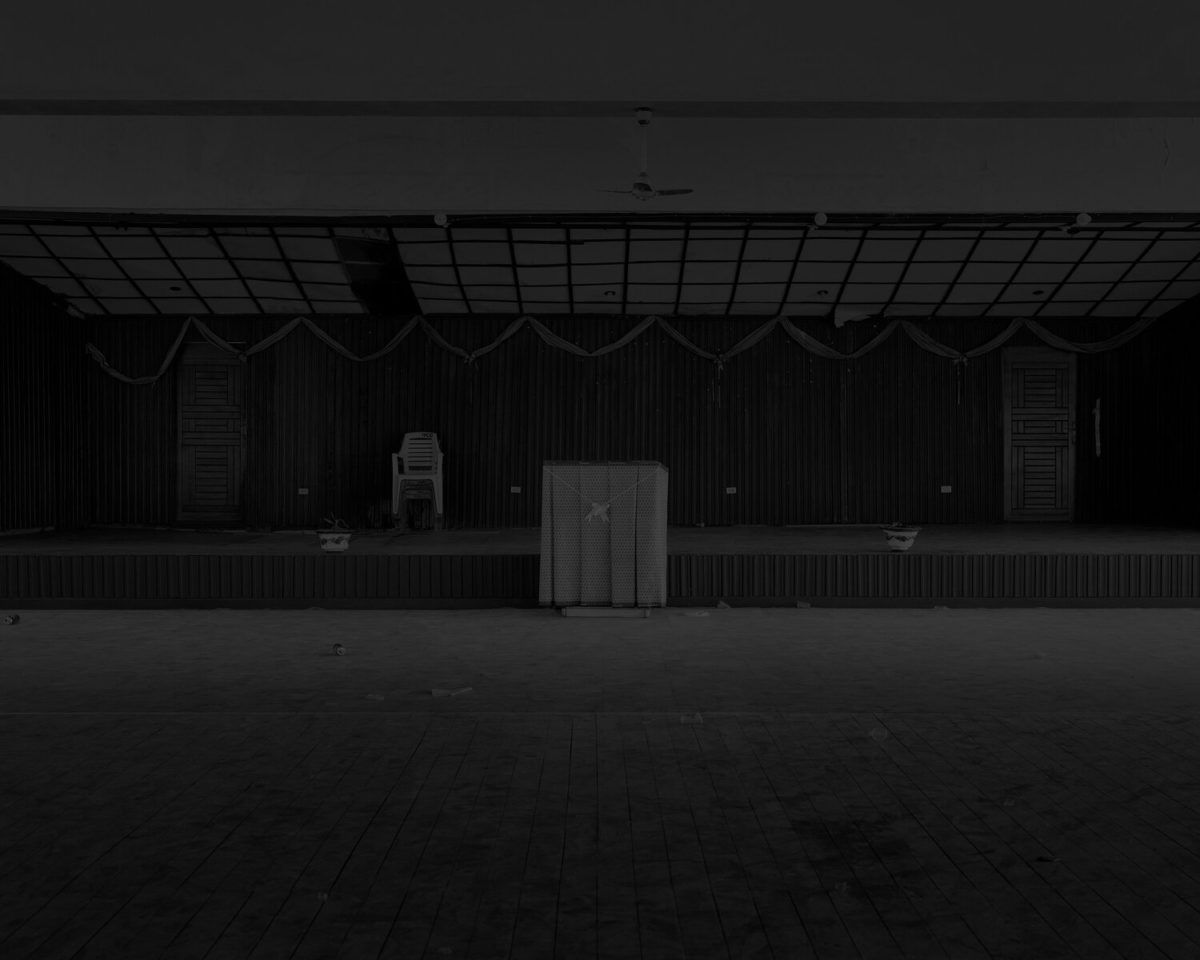

Verdier’s dark and enigmatic black & white images are contextual scenes which establish the settings for the color portraits. These solemn black & white images are his visual ‘equivalent’ to the silence of the night that is often featured in the witness’s accounts of trauma; a moment in time where their trauma becomes palpable and anticipation for the dawn, a symbol of hope, draws near.

The complicated layers of history and meaning in Reaching for Dawn prompted my need to learn more about why Elliott Verdier started the project, and discover more about the people he photographed and the backstory for the project. Elliott generously agreed to an interview to share more about the project and his creative process.

::

Somewhere in Grand Gedeh, Liberia © Elliott Verdier

Cary Benbow (CB): What compelled you to make this work for Reaching for Dawn?

Elliott Verdier (EV): I knew that a very bloody civil war took place in Liberia, but nothing much since. My vision of this region has developed over the years from films, documentaries, information gleaned here and there… When George Weah was elected president in January 2018, I thought it was surprising for a former soccer player. I looked into the country and its unique history a bit more and I found it fascinating.

I decided to go the first time to get rid of all my preconceived images of the country. I didn’t take any photos during my first trip. Wandering all around the territory and talking to people allowed me to define the story I wanted to tell, and that felt right to me and for the people of Liberia : the unspoken trauma (nobody had been brought to trial, no proper memorial has been built, no day is dedicated to commemoration) was carved into the population’s flesh, crystallized in the society’s weak foundations, that bleeds onto a new generation with a hazy future.

CB: What kind of stories do you wish to tell? What do you wish the readers take away from this project and book?

EV: I like to document places on the outskirts of global headlines. In Liberia, I also found very palpable themes I grew passionate about. Themes such as memory, resilience and generational transition. But what emerges from all these themes is our constructions as human beings, our determinisms… and how history influences our destinies and paths.

Of course, I would like to see Reaching for Dawn lead to a better recognition of what happened, but that’s a bit of a naive optimism. So I just hope I have been able to pull this story out of anonymity, these lives that flow away from our eyes, to keep a trace, a memory. It is an homage, a fraction of recognition the people of Liberia never got.

Jack and the abandoned Chinese boat. Robertsport, Liberia © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

CB: What do you feel are the obligations of a documentary photographer? Or what obligation do you have to the people in your photos?

EV: I have this impression that many documentary photographers in the past had more obligations towards the newspapers or institutions they worked for rather than the people they photographed. Maybe because the awareness of white privilege was less discussed in the public sphere. Today, the place of the photographer, of his or her gaze and methods, is becoming more and more important in the debate.

Earlier in my life as a photographer it often seemed to me that I was playing a role, as if I was adopting codes to belong to an ideal that I had forged for myself. These codes of an idealized photographer, which also belong to a collective, tend to reproduce pre-existing patterns. Not only do they bring nothing new to the field, but worse, they maintain some rotten roots made by power and underlying domination. During my first experiences as a photojournalist, deep down I felt uncomfortable, or even dishonest, towards myself of course, but even worse, towards those I was photographing. It was hard for me to put into words, to become aware of these patterns as the culture of photojournalism had built me up. In 2016, after a brief experience at AFP (Agence France Presse) covering the news every day, it became clearer and clearer to me that the methods of the agency and of the photographers around me did not fit with my beliefs. I had to change something, to take time. That’s when I bought my analog large format camera.

It is difficult to define a charter on the obligations of a documentary photographer because everyone has its own background, perceptions and criteria. The question of the legitimacy to talk about the Liberian post civil war, as a white, male, western photographer was primordial during the whole construction of the project. It was at the heart of many doubts, but encouraged me to think further about how to photograph and tell the story.

Later, I was lucky enough to have several people who defined my work as “honest”. And that’s just what I think my obligation is: to be honest with myself, towards those I photograph, and those who receive my images.

CB: Who do you draw photography inspiration from? Who are your early influences?

EV: As a young boy, I had several intimate experiences with photography, but the very first time I was struck by it was when I visited an exhibition of Richard Avedon’s work with my high school class. My admiration for his work never faded, and his influence has never left me since. There is something imperceptible, unspeakable, in the making of a beautiful portrait. An interiority that is both personal and universal. It’s wonderful to achieve such a fine balance with such technical mastery. This is something I also find in the work of Bryan Schutmaat.

I can also mention the social relevance of Deana Lawson, the poetry of Vasantha Yogananthan or the existential gravity that Jack Davison’s work inspires in me.

Adama and his mother Helena, Westpoint, Liberia © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

CB: Who are the people that appear in your photographs? Why are they more important than just being a figure in the landscape?

EV: The people who appear in my images are no more than figures emerging from the landscape. We all belong to the places we inhabit and that inhabit us. They are mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, daughters and sons, and directly or indirectly, they are all affected by what the country has been through.

When using a large format camera, I often had to explain what I was doing here: explain the purpose of my presence. People who appear in my photographs, often staring at the viewer, agreed to be photographed as part of the story I was telling. It’s as if they were carrying the narrative it in front of your eyes. They called for justice, and were in search of a recognition of their existence, of what they have lived.

CB: Do you see your work as documenting your experience or your environments, or commenting on them?

EV: I think it has to be both. You can’t simply photograph to document, your vision is driven by so many things you can’t control… it has to be personal. It has to be commenting. I just try to find the right balance. I would like the viewers to perceive that this is not an unquestionable truth, but rather an observation of a photographer in a situation he has perceived. Hopefully, it will make them want to dive a little deeper into the story, and who knows where it might lead.

Kemah and Jefferson, Slipway community, Monrovia, Liberia © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

CB: This work is specific to Liberia and its history. But how do you feel your work makes a comment on a universal level, as well as the personal level?

EV: One of the challenges of making this series was to get viewers interested. In Europe, we hear very little about Liberia because its history is closely linked to the United States… How does one interest people on a distant situation or topic they know nothing about? Giving the project a more personal approach allowed me to move away from the more classical representations that have wearied, or at least accustomed, the viewers. A perception that no longer surprises makes people lose interest.

I told myself that, working on a specific country, I had to explore more intimate things that paradoxically speak to everyone; to touch on subjects which connect our lives as human beings. That’s the way I try to create connections, empathy.

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

The courtroom of Harper, Liberia © Elliott Verdier

CB: In the press release for Reaching for Dawn, you write: “The dark and enigmatic monochromes are contextual images that establish the setting for the color portraits. These black & white images are a reference to the night that so often appears in witness accounts, a moment in time where the trauma becomes palpable. They distill a heavy atmosphere that spreads the suffocating silence over the country. From this silence, words emerge, transcribed onto fragile paper, to haunt the Liberian night with inaudible whispers.”

This leads me to wonder or infer, as with the darkly printed images made by Dawoud Bey in his project, ‘Night Coming Tenderly, Black’ – are your dark images the evocation of a dreamscape, or these dusky tones could possibly be employed to call forth affective rather than factual realities and to make the viewer aware that documentary “truths” were not your intent?

EV: I’m pleased that you mention Dawoud Bey’s work which, when I came across it, obviously touched me. I also like this expression you use, that of affective landscapes. It seems to me particularly appropriate for this project. These dense b&w from which ghostly silhouettes sometimes emerge are the metaphorical reflection of an endless inner night from which the color portraits arise. About it the Franco-rwandan writer and singer Gaël Faye writes way better than me: “Justice is not simply a stage towards reconciliation. It is a mystical quest for those women and men who have lost everything. And this search for truth becomes a promise in itself. Suddenly, it is no longer a question of viewing Liberia exclusively through the lens of its wounds, but above all of seeing all the grace that radiates from its struggle for life, the same life that escapes the dark night in search of dawn.”

CB: Let’s talk about how you choose to depict the elements of nature, wildlife, landscape, man’s inclusion/interaction with nature in your work. Why you choose to depict these elements in the way you do?

EV: These elements of nature are primarily topographical: Liberia is waterlogged and covered with thick jungle called bush. Water, first of all, is a recurring theme in the series because its symbolism (both life and death, purification, renewal and religion) provides many clues to the subject. I went to the country each time during the rainy season to get in addition to the water a particular atmosphere with dark and cloudy skies. The lushness of the bush evokes both a form of chaos and renewal, but also time. Time, because where the image of war is one of destruction, the image of regrowth shows the time of appeasement.

CB: Was it difficult to start and stop working on projects that involve people in need?

EV: It was difficult to start because it was hard to find my place. It was hard to find the right words. But I was very surprised by the way people opened up to me. I was expecting to hit the wall of over 15 years of denial and silence. But their words were very close, all I had to do was listen. Then I guess the project will never stop completely, I may not make any more pictures, but I will continue to make them talk.

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

From Reaching for Dawn © Elliott Verdier

CB: Amidst the striking images in Reaching for Dawn, there are also passages of graphic, brutal violence printed in the book. Please tell me about the process of hearing these stories from the people you met.

EV: I made the audio testimonies in a recording studio in Monrovia, the capital. With the help of Archie (who assisted me greatly), I gathered 14 people, 7 former executioners and 7 victims, all from Westpoint, the largest slum in the country, and an emblematic place of the war. These people are neighbors. They told us about the war and how they have lived it since. Recording lasted one day, and it was intense to say the least. The images are never graphic, but the testimonies are rough. They carry within them the naked truth of those who speak. That’s what is important. I had to give a voice to the people I was photographing. Their words with their voice, their intonation, their breathing.

When we arrived the studio light bulb went out. So when they entered the studio one by one, we were in the dark. Which, I think, helped many to share their feelings, but for me it was very trying and, to tell you the truth, terrifying. That day, as usual, I came back home with my friend Maxime who assisted me all along, I don’t remember that we exchanged a word of the evening. I think that one feeling will ever last, but as for them, if I’m honest, how will I ever know what they deeply felt sharing their experience ?

CB: Did you keep a journal during this project? Do you keep notes or write about the places and people you see? If so, would you share a meaningful entry?

EV: I didn’t. At first, I always regretted not doing it. But I know that it costs me too much. I wish I could, but now I know I can’t. When I don’t make images in those moments, I think about them. I don’t have the courage to write. I did a bit afterwards though, and wrote this:

“Wherever I laid my eyes, and more than anywhere else, I could see the unfolding of the path that had led them to this point. Their history. It felt as if it had melted all over them, imbuing up to their most intimate certitudes. As I roamed by all these anonymous destinies, I perceived characters eroded by former rain. They carved these warm mangroves, a mire of existence apparent to a silent night, the type that lingers as we wait with resignation for dawn and its saving light. Today, I often ask myself what story determines my gaze and dictates these words. My photographs are illusions of my reality which try, with all my sincerity, to seek a universal truth. From this meeting with the night, from this glimpse, is born this attempt.”

::

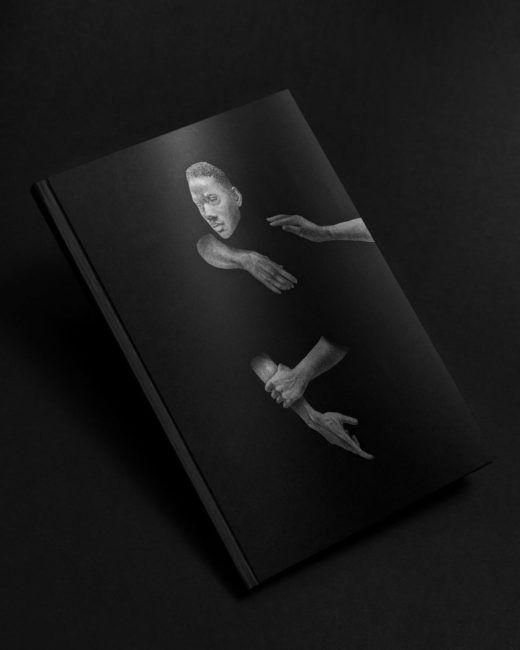

Reaching for Dawn by Elliott Verdier

Published by Dunes

www.dunes-editions.com

@dunes.editions

Texts: Gaël Faye, singer-songwriter, rapper, writer Leymah Gbowee, activist, Nobel Peace Prize laureate (2011)

Illustration: Sacha Von Villard

Graphic Design: Marion Denoual

Translations: Sarah Ardizzone Géraldine D’Amico

Bilingual English & French

152 pages

66 photographs (36 b&w – 30 color) Format: 24 x 31 cm

::

Elliott Verdier is a documentary photographer driven by themes such as memory, generational transmission and resilience. He is based in France.

In 2017, he completed his first long term project, A Shaded Path, in Kyrgyzstan. He was helped by the French National Center for Visual Arts in 2019 for his second major project Reaching for Dawn in Liberia.

Elliott Verdier also regularly collaborates with the press, notably with the New York Times and M Le Monde Magazine.

elliottverdier.com

@elliott.verdier

Location: Online Type: Book Review, Interview, Landscapes, Portraits

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply