blog

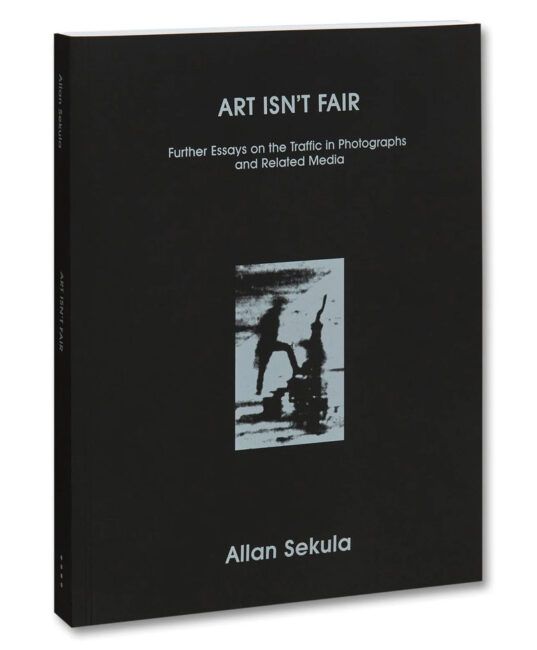

Book Review: A Photographer and a Writer: A Review of Allan Sekula’s Art Isn’t Fair

Photography lacks a tradition of serious writing. This is most evident in contemporary photography, where we have a mountain of photographs and virtually nothing serious written about them. What writing we can find most often is nonsense written by people with little to zero knowledge of art history, theory, or criticism. That is, what we tend to find are “blog style” writings by amateur photographers looking to gain a following on some social media channel or, worse, some photographer trying to explain their own work. As Alan Trachtenberg once claimed, “Photography has seemed to inspire as much foolishness in words as banalities in pictures…” and I couldn’t agree more.

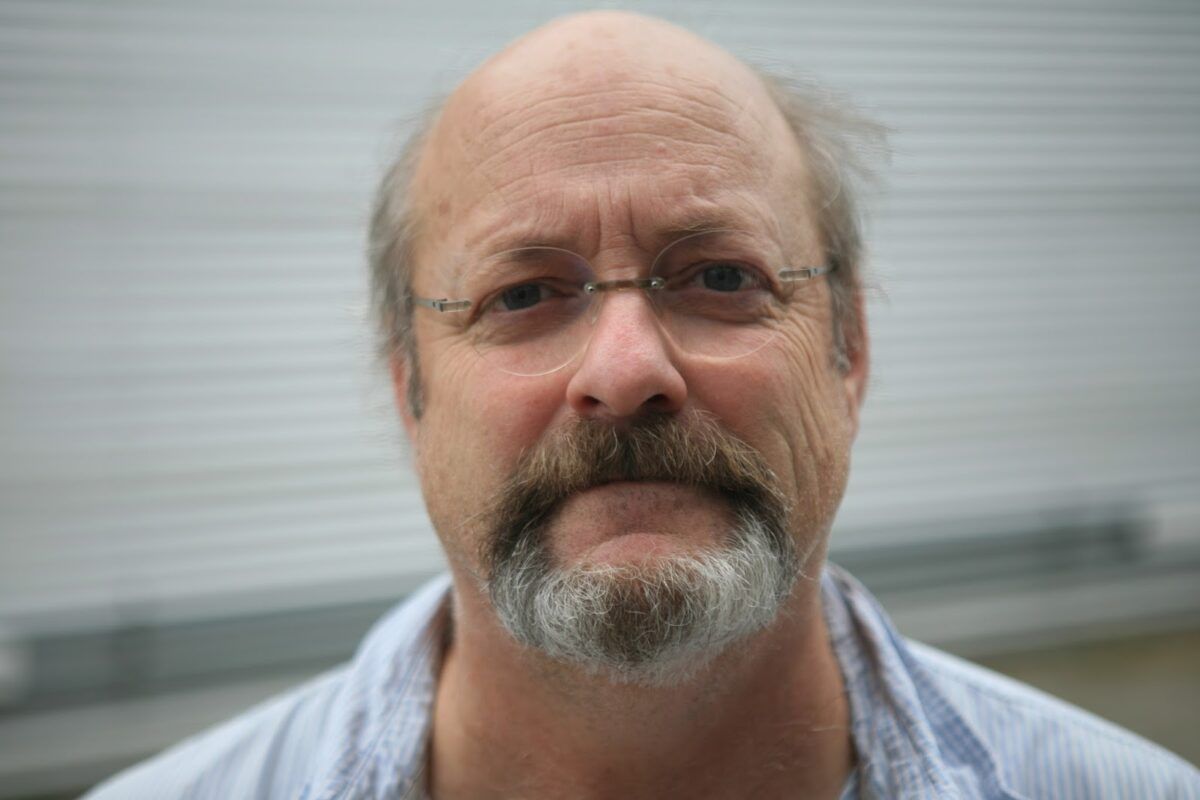

Allan Sekula, on the other hand, is one of those rare animals that can both photograph and write seriously and smartly about photography. Although not necessarily always writing criticism, especially of the work of others, he did write extensively about his own work. This is an important step in the right direction, as intelligent and informed writing (as opposed to the drivel we most often get today) about one’s own photography adds an additional layer of meaning. This layer then provides raw material for critical writing, whether immediately or decades down the road. With this in mind, this new volume from Sekula’s estate provides a wealth of his writing – a feast for any curious mind, but especially useful for a new generation of photographers who are less acquainted with the art of enlarging images with the written word.

Allan Sekula

It is important to note that Sekula does not simply write about his photographs. That is, he is not writing descriptive captions or explanations but rather essays that elucidate the context in which his photography is made or in which it might be viewed. His words are companions not appendages. Sekula’s essays can, technically, be read and understood – enjoyed even – in the absence of the photographs. As this is a “collected works” volume, Sekula’s subjects are wide and varied – any attempt to coherently and succinctly summarize the content of the book would be folly. Some of my favorite readings, however, were his comments on Canada, generally, and on Canadian unions and workers, more specifically. As a Canadian myself, I was pleasantly surprised to find this connection. Despite being American, Sekula published his first collection of photographs, alongside his early critical writings, in a volume from the press at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in 1984. My aunt, Canadian painter Susan Sweet, received her art degree from this same college, and I do have memories of roaming the halls at NASCAD as a small child. Sekula also writes about Sudbury Ontario, opening the essay with:

“What can I tell you about Sudbury? I have neither the knowledge nor the inclination to write a tourist guide. You can, if you want, take a bus from Ottawa, leaving at midnight and following the Trans-Canada Highway through the granite outcroppings and evergreens of that vast glacial pathway, the Canadian Shield. You’ll arrive in Sudbury by dawn if it’s summer, before dawn in the winter. And if you are simply scouting about, as I was on my first visit, you can photograph all day and into the evening and catch a night bus back to Ottawa, arriving at four or five the next morning. My face bounced against the vibrating bus window as I slept, and so I returned with a black eye.”

As one can see, Sekula’s writing can be very accessible, almost “charming” in places, such as in this passage from his musings on Sudbury. In other places, Sekula flexes his very much developed intellectual muscles more conspicuously. Here is an excerpt from his Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea:

“Five or ten years ago, I was confident that the sea had disappeared from the cognitive horizon of contemporary elites. Now I’m not so sure. The sea returns, often in gothic guise, remembered and forgotten at the same time, always linked to death, but in a strangely disembodied way. One can no longer be as direct as Jules Michelet was in his 1861 book, La Mer, which begins with the blunt recognition of the sea’s hostility, its essential being for humans as the ‘element of asphyxia.’ And yet Bill Gates buys Winslow Homer’s morbid ‘Lost on the Grand Banks’ for more money than anyone has ever paid for an American painting.”

As readers are warned in the foreword, “IF SEEKING A QUICK SHOW-AND-TELL, BEST TO TURN BACK OR ELSE FORTIFY YOURSELF.” Sekula’s writings are not for the faint of heart or mind. The writing can be dense and the topics fluid, to say the least. But if you are looking to see beyond the visual surface in photography and are willing to do the work, Sekula’s writings can be highly rewarding. He has a curious mind and works hard at both thinking and seeing and bringing both to us, his audience, with brilliant clarity. With graduate work in both the practice and theory of photography, Sekula is able to bring authority to both his images and his words in a way that not many photographers can replicate.

Sekula’s Images from in front of Bill Gates’ home in Seattle.

Photography needs words. In our visually-choked modern existence the image is not enough. We are inundated with the visual and are rarely impressed. But there is a space that still exists for the photographic artist to leave a mark – a space overlapping between the words and the image – a space where we surely find the likes of Allan Sekula and his works. Returning to the words of Alan Trachtenberg, “And it is evident any new developments in photographic criticism will require that critics take into account the communicative power of the photographic image, its ‘language’, its ‘meaning’, and the relevance of that meaning to our world.” This is precisely what Sekula was doing. He was acutely aware of the interplay between words and images for closing the gap between the image and its meaning, and connecting that meaning to our world.

Sekula is clever with words, too. He is a good writer. As one might find layers of meaning in a good photograph, one may also find such layers in Sekula’s writing. The more you bring to the book, the more you will find. The book is, as I have said, not a lightweight reading experience. There is complexity and depth even in the simplest words when woven together by Sekula’s pen. Take, for example, this excerpt from his letter to Bill Gates:

And as for you Bill, when you’re on the net, are you lost? Or found?

And the rest of us – lost or found – are we on it, or in it?

“Art Isn’t Fair” by Allan Sekula stands as a bastion of photographic intellect. Those who delve into Sekula’s work will struggle to revert to mindlessly capturing the world around them. Even the most self-absorbed photographer will find it silly to merely contribute another image to the world without considering its deeper significance, its raison d’être. Photographs have power, they influence our world in ways that are complex and political. Sekula’s cautionary note rings clear: tread carefully with what you unveil to the world through your photography, for you might reveal more than you intended—perhaps, that you have nothing to say.

Art Isn’t Fair: Further Essays on the Traffic in Photographs and Related Media

by Allan Sekula

Sally Stein, Ina Steiner (eds)

Published by MACK

Location: Online Type: Book Review

One response to “Book Review: A Photographer and a Writer: A Review of Allan Sekula’s Art Isn’t Fair”

Leave a Reply

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Possibly one of the most intriguing reviews of any book, let alone one revolving around photography, I’ve read in quite a while. And, while on the subject of photographic criticism: If I try hard to recall the names of critics I’ve read and respected, I can sadly recall only one at the moment: A.D. Coleman. Sometimes I disagreed madly with his writings, but could always respect his acumen, as well as his serious dedication.

I will definitely be looking up Sekula’s book.