blog

Book Review: Daily Self-Portraits 1972-1973 by Melissa Shook

I have spent a considerable amount of time with Melissa Shook’s newly published, though posthumous, Daily Self-Portraits 1972-1973. Initially, I found myself at a loss for words, uncertain of how to engage with this collection. In an era where ego often eclipses artistic intent in photography, Shook’s self-portraits present a challenge. Though they hail from the 1970s—a period of innovation and experimentation—the contemporary eye is weary of the camera as a reflective tool. This initial reaction, however, felt too simplistic.

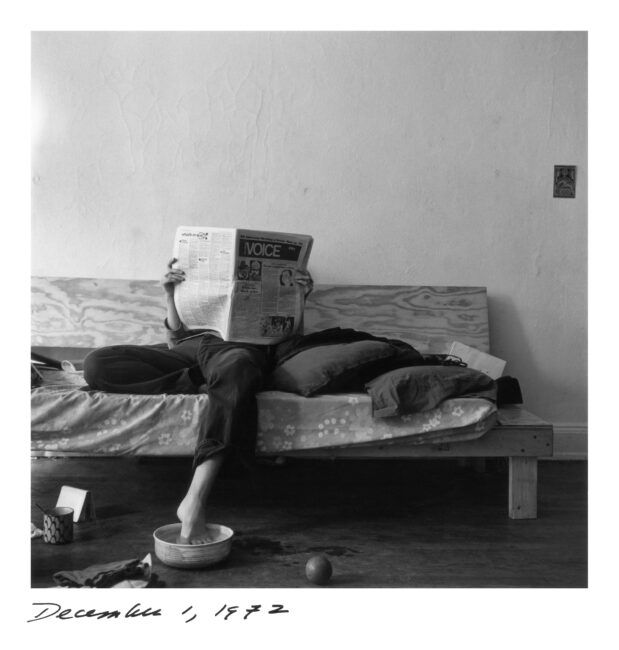

© Melissa Shook, 2024 from the book Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973. Courtesy of TBW Books.

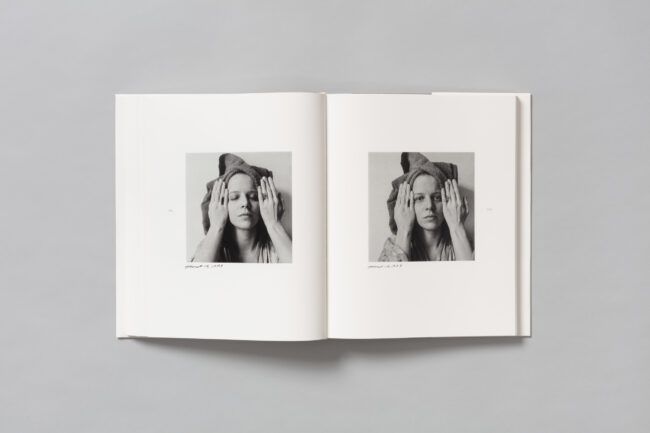

So I continued to delve into the book. Weeks passed, and the image of the towel-wrapped head on the cover began to resonate with me, drawing me into its narrative.

To appreciate Shook’s work, one must momentarily step back into the 1970s and set aside the intervening decades. The unique quality of these photographs becomes apparent when viewed in the context of their time. While the camera has long turned towards its operator, Shook’s self-portraits are distinct in their self-reflective quality. Lee Friedlander had already begun exploring this territory with his 1970 publication Self-Portraits, but his approach was more about being “in” the frame rather than being the frame’s subject. Around the same time, Francesca Woodman also turned her lens inward. Sally Stein, whose essay in the book is both insightful and erudite, suggests Shook’s work predates Woodman’s. Although Woodman’s earliest self-portraits are generally dated to 1971, it is the shared exploration of self-portraiture by both women that holds greater significance. Personally, I find Woodman’s work to be more intricate and profound. Yet, Shook’s images, though simpler, possess their own beauty and narrative, deserving their place in the spotlight after five decades.

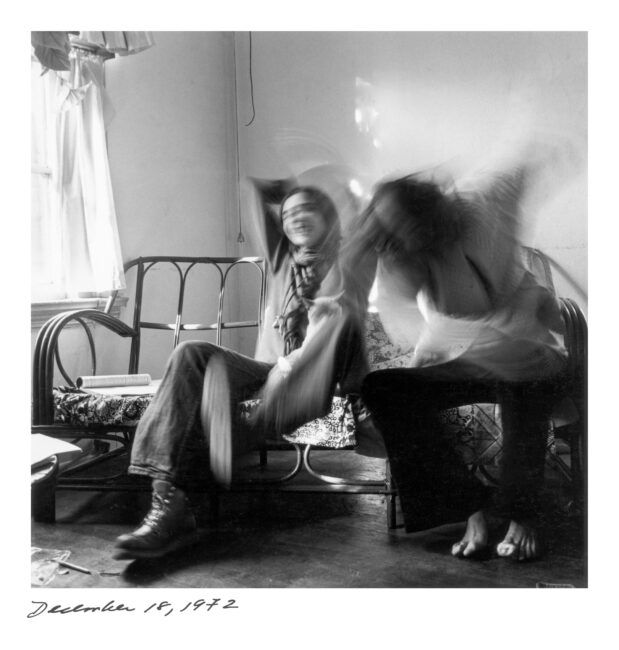

© Melissa Shook, 2024 from the book Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Woodman’s photographs are potent, standalone pieces. In contrast, Shook’s self-portraits, as Stein notes, function as a cohesive narrative. Initially, the images felt familiar, perhaps even derivative. However, if seen in their original context, this sense of déjà vu might not have occurred. Nevertheless, today’s viewer must reconcile these images with contemporary sensibilities. Viewed individually, the collection may seem underwhelming, but when considered as a whole—with Stein’s contextual essay—they coalesce into a more powerful narrative. Shook’s story, as depicted through her photographs, reflects her struggles as a single mother, from images with her daughter to blank images that represent the days she was unable to create. The narrative, though imperfect and indistinct in its beginnings and endings, gains autobiographical authenticity and depth.

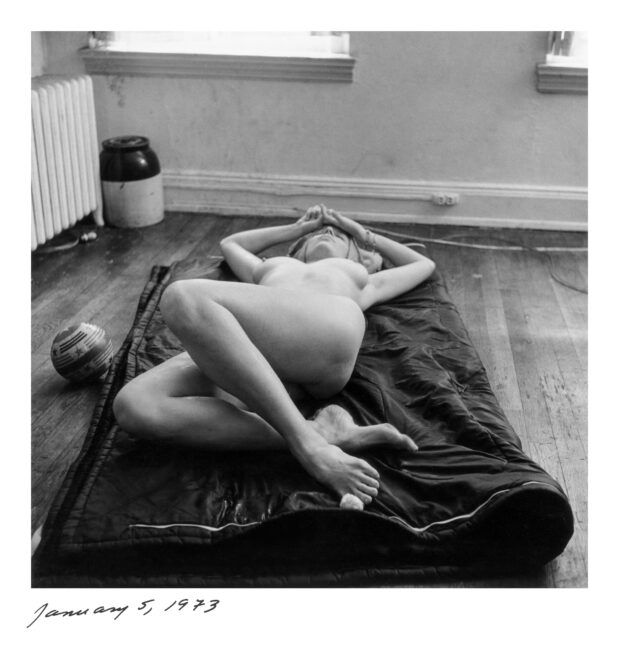

© Melissa Shook, 2024 from the book Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Despite the adversities Shook faced, her photographs exude a certain playfulness. The opening image, for example, shows her foot submerged in medicated water—a remedy for a toenail problem. Yet, the photograph, despite its medical context, is imbued with a subtle playfulness. Shook’s face, obscured by a copy of the Village Voice, invites speculation about her mood, though I sense a quiet humor beneath it. This approach resonates with the way Kurt Vonnegut balanced the grim realities of war with the absurdities in Slaughterhouse-Five. Similarly, Shook manages to convey her narrative’s heaviness with an approachable and engaging tone, a quality evident from the very first image and maintained throughout the collection.

© Melissa Shook, 2024 from the book Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Stein’s essay is a crucial component of this collection, providing necessary context. While it does an excellent job of framing Shook’s work, it occasionally ventures into interpreting Shook’s artistic intentions and process, a risk that can sometimes overshadow the artwork itself. For me, it would be preferable to approach Shook’s self-portraits as a playful engagement with her craft, rather than seeking an overly complex or profound artistic manifesto.

© Melissa Shook, 2024 from the book Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Ultimately, Shook’s book is a beautiful and intriguing volume—a testament to the many talented photographers whose work might not have redefined aesthetics but nonetheless holds significance. While Stein’s essay suggests deeper meanings, the collection itself feels grounded in the everyday experience of an artist committed to her craft. It is a volume of daily self-portraits that reflects the dedication of an artist navigating the intricacies of her daily life. Why demand more than this?

© Melissa Shook, 2024 from the book Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Daily Self-Portraits 1972-1973

by Melissa Shook

Published by TBW Books

Linen flexicover with French dust jacket 400 pages, 198 duotone plates

8 x 10 inches

Essay by Sally Stein

ISBN 978-1-942953-61-6

Location: Online Type: Black and White, Book Review, Portraits

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply