blog

Book Review: Russian Rust Belt by Alan Gignoux

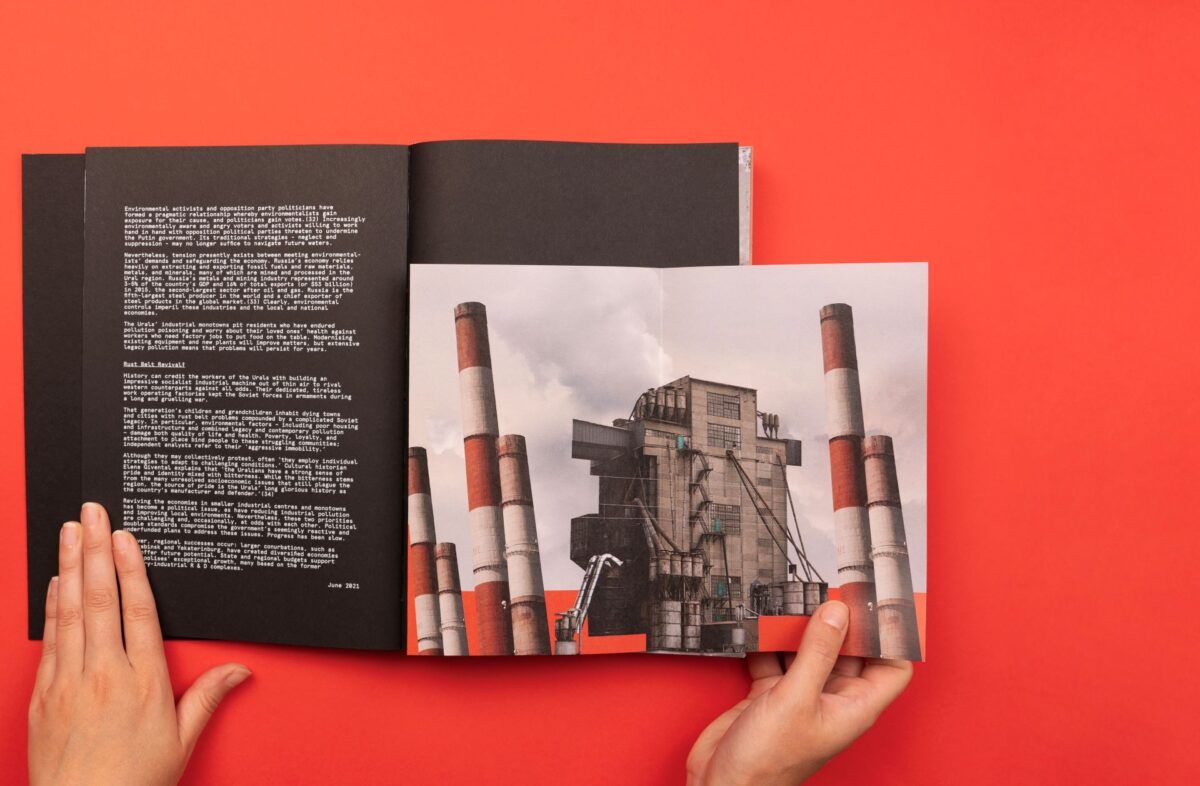

Uralvagonzavod Factory, Nizhny Tagil, Sverdlovsk Obast © Alan Gignoux

In the heart of Russia’s Ural Mountains, a forgotten world unfolds. London-based photographer Alan Gignoux embarks on a journey through a post-industrial wasteland, capturing the remnants of a bygone era. His photographs are are haunting elegies of a past world order.

Gignoux’s work, a testament to the human cost of economic decline, is more than just a visual record. It is a visual conversation with history, politics, and the enduring spirit of the human condition. Through his lens, we witness the stark contrast between the grandeur of Soviet-era industrial might and the desolate landscapes that now bear its scars.

His images are not simply aesthetically pleasing (which they are) – Gignoux’s work is an invitation to contemplate the profound impact of industrialization on both people and place. As we delve into the pages of his book, we are faced with abandoned factories, polluted rivers, and the weary faces of those who have borne the brunt of economic hardship. Some of those faces may be fighting on the front line of a conflict between Russia and Ukraine currently. Do the people we see in these images have the same lives now as they did fifteen years ago? Are their lives better or worse now? Did they, Do they, feel oppressed? Was the totality of their lives ever going to be different due to the template of history laid down for them to follow?

The parallels between Gignoux’s exploration of Russia’s rust belt region and the post-industrial landscapes of the West are striking. Yet, his project offers a unique perspective, revealing the nuances of a culture shaped by a distinct historical context. Through the images in this project, we gain a deeper understanding of the shared struggles faced by workers in both the East and West, transcending the boundaries of geography and ideology.

Textile Factory, Ural Mash, Sverdlovsk Obast © Alan Gignoux

Teenagers, Irbit, Sverdlovsk Obast © Alan Gignoux

Wedding Guest, Ural Mash, Sverdlovsk Obast © Alan Gignoux

Gignoux’s commitment to his craft is evident in the meticulous attention to detail he brings to his work. He is not satisfied to merely record the physical decay of industrial landscapes; he seeks to capture the emotional and psychological toll that such decline takes on individuals, communities, or dare-I-say hemispheres. His photographs are infused with a sense of empathy and compassion, inviting us to connect with the stories of those who have been marginalized by the forces of globalization and economic change.

As a reader views the pages of Alan’s work in Russian Rust Belt, we are struck by the timeless quality of his images. The ‘every man’ aspect of his portraits is almost universal – or the equivalent of every working person in a place where one makes their living from the sweat of their brow. Studs Terkel would’ve said, these are ordinary people who did extraordinary things. Through his photography, Gignoux has created a lasting legacy, a powerful reminder of the importance of remembering the past and confronting the challenges of the present – while shining a spotlight on these industrial landscapes and their workers.

A commonality between the Appalachian region and the Urals struck me after viewing this project. The same applies to West Virginia as it does to Karabash: There used to be jobs here, and now there are not. American workers who were recently promised a return of jobs in the coal industry didn’t experience a revival. Unfortunately, jobs in sectors of the Russian economy connected to the war, like textile and lathe workers, have returned for the time being. Russian workers who have not used their skills since the 1990s are returning to lucrative opportunities. The revival of certain industries in these areas raises conflicting attitudes and opinions for people who might be hesitant to support the war, but have been in economic decline for decades.

I had a conversation with Alan Gignoux, and a few of the people who brought Russian Rust Belt to life. Chloe Juno and Jenny Christensson also worked on the project as editors and/or designers – and all three agreed to an interview to discuss aspects of the project. As with Alan’s 2022 project, Mountaintops to Moonscapes, a great deal of planning and attention in the design phase of the book has resulted in a treasured book on my shelves. A great deal of planning and thought went into creating the work in RRB. When Alan took the photos 15 years ago, he had to decide how to present images and ideas which contained multiple layers of meaning. Now, over the past couple of years, he is faced with how viewers see the work in the light of the war between Russia and Ukraine. The project admirably tries to reconcile multitudes of meaning, even if is is tantamount to finding the harmony of wind chines in a hurricane.

::

Cary Benbow (CB): Does where you grew up and spend your formative years influence the way you work on projects, or the subjects you take on?

Alan Gignoux (AG): I grew up in London: The Cold War was raging, and we were discussing what to do if World War Three erupted as GCHQ was just down the road and loomed larger than life, leaving an impression on everyone. World politics were in the air. Politics and other world issues were freely and fiercely debated at the dining room table. I think I can say with confidence that my interest in politics and the state of the world germinated in the cut and thrust of the conversations during those early years. I also went to boarding school from the age of eight, which I think has made me quite independent and resilient – I’m quite happy setting out on my own into the unknown and navigating all sorts of environments.

CB: What kind of stories do you wish to tell with your projects or your art?

AG: I have two areas of interest: the environment and refugees. I want to tell stories about how economic and political motives impact ordinary people. My projects involve storytelling but are also panoramic explorations of complex problems facing the world today and their human cost. I begin my projects with an idea or a concept, but I don’t form my narrative vision until I am on the ground. I am endlessly fascinated about the big issues confronting the world and passionate about using my photography to bring those issues, in all their complexity, to people in an accessible way.

CB: What makes photography your choice of expression?

AG: I began my career in entry level positions in journalism working in the UK and South Africa. In South Africa I started photographing as an amateur; a journalist colleague liked my work and commissioned me to take the photographs for one of his features. Although I slipped into professional photography in this way, I recognise that it is a natural medium for me to explore my curiosity about the world. I am not a words person – I prefer the open-ended nature of photography which can say much in a single image and yet always leaves room for interpretation.

CB: In your opinion, what makes a good photograph?

AG: Of course the technical thirds rule is what makes a good photograph: an image that directs the eye to focus on what the image is trying to say, what provokes you, influences you, and possibly makes you question your assumptions. However, a photograph is not just the result of technical factors, it is also the product of the photographer’s lived experience and knowledge. I believe that all the research and reading I do informs my work and makes it stronger.

CB: Can you please talk about the ideas behind your images in Russian Rust Belt? How does it relate to your other projects, or how are they significantly different?

AG: RRB is like my other work in that it explores the impact of heavy industry on people and the local environment. A key difference is the fact that I don’t speak Russian and am not personally familiar with Russian culture, so I took those photographs with an outsider’s perspective. It’s worth noting that RRB precedes both Oil Sands and Appalachia and was in fact my first introduction to photographing industrial landscapes, although I was already at the time interested in de-industrialisation as a political and economic issue. Worth noting also that the RRB book was made with a significant time lag between the taking of the photos and the making of the book, while Oil Sands and Appalachia were made within two or three years of taking the images.

Advertising Banners, Nizhny Tagil, Sverdlovsk Obast © Alan Gignoux

Karabash Old Town, Chelyabinsk Oblast © Alan Gignoux

CB: Your work in Russian Rust Belt is specific to a certain place and time, and yet it has a lot in common with other work you’ve created. ‘Mountaintops to Moonscapes’ has a direct connection to RRB, and on some level I feel a viewer might have a hard time telling a difference between some images taken from both projects. For you, is the RRB work isolated to the people and place of the Urals?

AG: In making Russian Rust Belt I was interested in the similarities and differences between the post-industrial experience in the West and in Russia. In many ways, the impact on communities has been similar and people are battling with comparable problems. There are parallels in the ways in which post-industrial regions have had to contend with legacy pollution. I thought that looking at these similarities might start conversations which would open the door to deeper mutual understanding, if only in the relatively small world of photography and photobooks.

CB: What do you wish the readers take away from your project/book?

AG: How the human experience is similar despite historical (and now present day) political differences. But also, I would like them to understand the specific hardships that people in post-industrial towns in Russia have had to confront (issues related both to the Soviet era and the Putin regime). I hope that my book will encourage discussion about what governments all over the world can do to rejuvenate old industrial communities to reduce human suffering.

CB: Ordinary people are the subjects in RRB, but the events after the Russian invasion in early 2022 may change how viewers perceive the people and activities in the book – and might even question the intent of the project if they don’t consider the timeline of creating the work and the book. How do you reconcile the project against current events?

AG: The photos were taken in 2009 at a very different time – they are now a piece of history. I think people can understand that I was documenting a particular environment at a specific point in time (how we see those images is naturally affected by events in Ukraine, and perhaps it is interesting to think about the space between the relatively optimistic time in which the photos were taken and my assumptions then and how we see the images now, after the invasion of Ukraine).

Armenian Taxi Driver, Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Obast © Alan Gignoux

CB: How do you describe your photography to someone who’s not familiar with it?

AG: I would describe my work as documentary photography with an emphasis on long form projects. In a single project I often work with both still and moving images, and I may share my work with the public using photobooks, films, or exhibitions – or often a combination of all three. I am building my environmental projects into a comprehensive umbrella body of work titled Bruised Lands. I do tend to see each project as a building block contributing to a complex whole that will eventually embody my life’s work.

CB: As editors and designers for the project and the book, what aspect or story stood out as very important to showcase?

Jenny Christensson (JC): We were struck by the geographical scale of the project and the relatively short timeframe within which Alan completed the residency. We wanted to convey the way in which Alan worked – moving quickly and recording his impressions. We were also struck by the bleakness of the landscapes against which the people Alan photographed were living their lives. We wanted to capture something of the experience of living amidst decaying industry and rust belt style economic decline. We were interested in the similarities and differences between the Ural industrial region and rust belt regions in other parts of the world, eg. the USA. We also wanted to highlight the contrasts – the signs of a new economy emerging from the ashes.

Chloe Juno (CJ): We also put ourselves into the shoes of the people in the photos imagining what it would be like to have a factory puffing and working at the top of our streets, we talked about about a strength of character that comes through in some of Alan’s portraits and how it could be the same streets we tread, how Alans camera feels like us walking, his eyes are our eyes. We talked about the universal journey to work. I think also the share scale and power of the factories and that’s why they exist on some pages as DPSs. I felt looking at Alan’s work, it’s an incredible record of time and coming to the work with a certain view of Russia having never been, I felt I learnt so much more and empathised with the people living in an industrial setting and it made me think of how England would have looked and felt like many years ago. On a personal level as a picture editor, I have also spent time as a photographer documenting, old working laundries, old industrial markets, Toshiba television factories, bus station workers in England, my mind flipped back to those locations. I have also in the past worked in similar places. One thing that also comes to mind as we were thinking about the world of work at a time when so much had shut down and we were unsure how the future would look.

CB: Let’s talk about the steps the project took from first edit to the final book layout. What challenges did you overcome, or what paths did you take which were not planned?

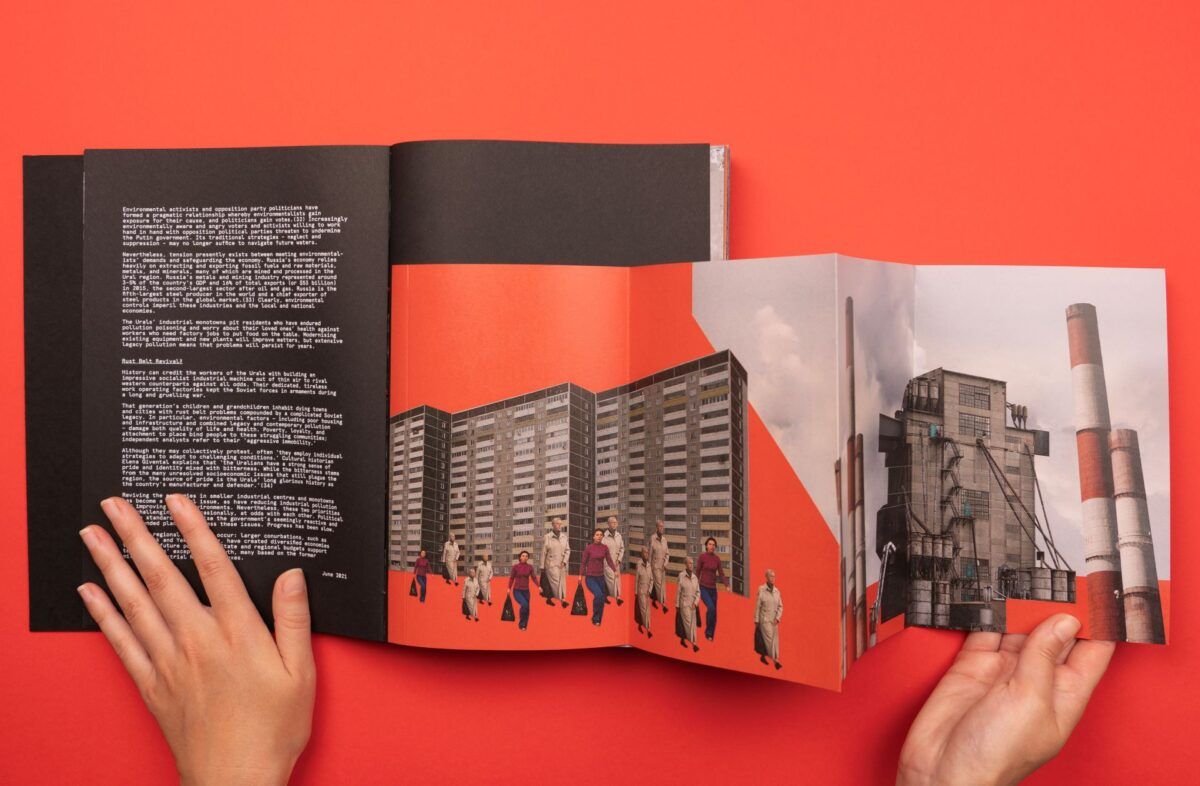

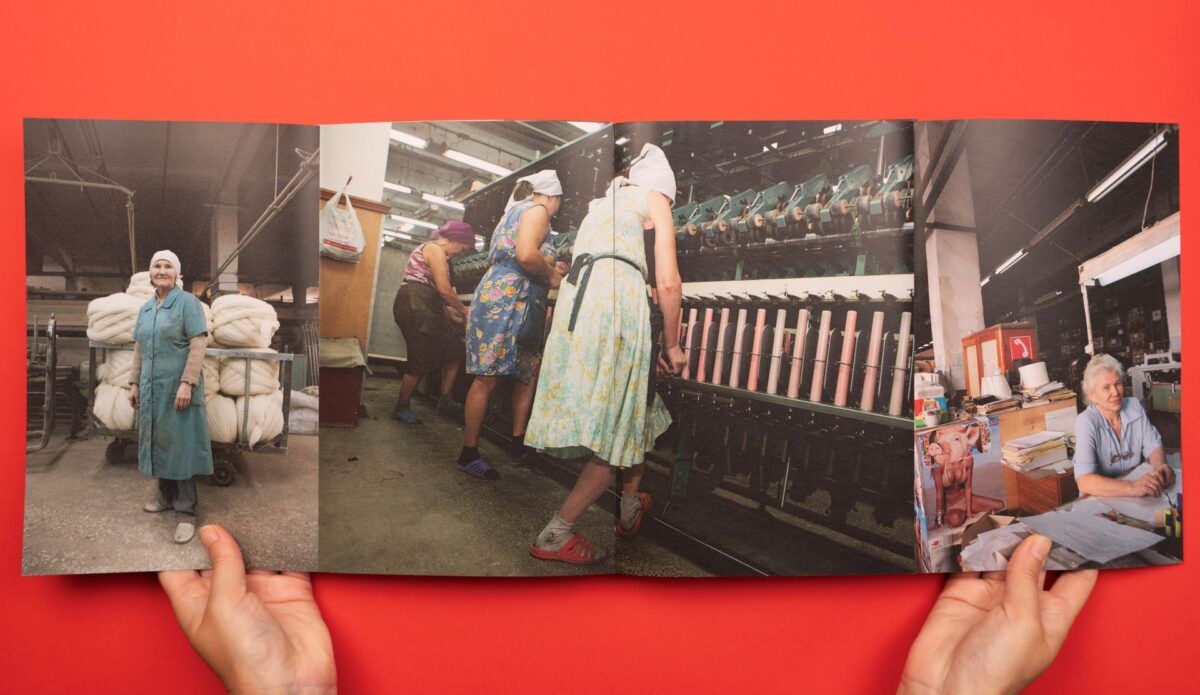

JC: We began the editing process for this project during the first Covid lockdown and the entire editing process was done online during the pandemic. We went through Alan’s online archive for the 2009 project, which had gone through earlier edits and was therefore a little confusing, as many images were duplicated across folders. Initially, we organised the folders into locations and subsequently we looked at the material in terms of categories eg. work, factories, transport, industrial decay, pollution, residential buildings, portraits, street photography. Our book designer, Emily, worked on an initial concept looking at the working day, but we abandoned this approach as we felt there was not enough material and it meant we would be excluding images that we felt were important. We explored the idea of presenting the material city by city, but, again, there was a wide variety in the number of images Alan had taken in each place, leading to unsatisfactory imbalances in the edits. In the end, we decided to present the images in a way that reflected Alan’s photographic approach. We chose an impressionistic sequencing that moves backwards and forwards between locations, driven mainly by the content in the photographs and the way one image leads to the next using visual cues. Inspired by Chloe’s copy of Hardened, by Jeff Mermelstein, we decided to create a build-up of many images, piling on impressions. We anchored the sequencing by inserting the gatefolds, each of which has a landscape photo that opens to show the interior of a factory, giving the impression that you are walking into a factory from the outside.

The book went through several titles 1) Industreality 2) The Dirtiest Room 3) Russian Rust Belt. The second title is from a quote from Yeltsin’s environment advisor (which you will have seen in the book, we kept the quote, but didn’t use it as the title). We decided on Russian Rust Belt, because it included Russia in the title and because our interest in the project extended beyond environmental themes to include economic issues. We also wanted to draw people’s attention to the common experience shared by workers in post-industrial capitalist and communist economies.

CB: What choices were made to come up with the cover binding style, the pace of the images and chosen regions/sections featured in the book, and the decision to use gatefolds in the way you did?

JC: Regarding the binding, our first dummy featured a spiral binding, which we all liked. It was also a little larger. After Covid prices for printing soared and we were forced to rethink the design. This resulted in the current binding and the smaller book page size. Either way, the binding was designed to allow the book to lay flat when open so that people could more easily appreciate the photographic pairings.

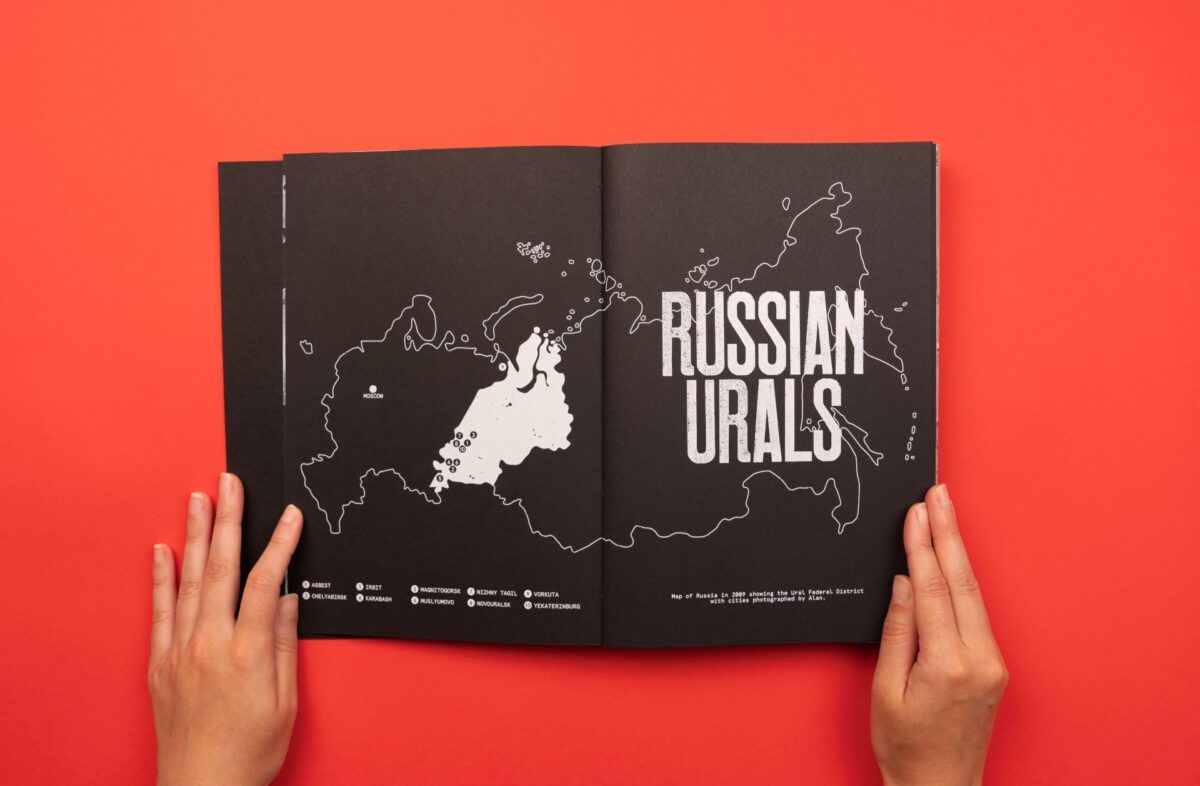

The cities featured in the book were those visited by Alan – we chose to create the city bios (as we called them) as we realised that most people know very little about this region of Russia. We felt that the one-page bios would give them enough background to form an impression of the industrial base built up under communism and the rate of decline of industry in each place.

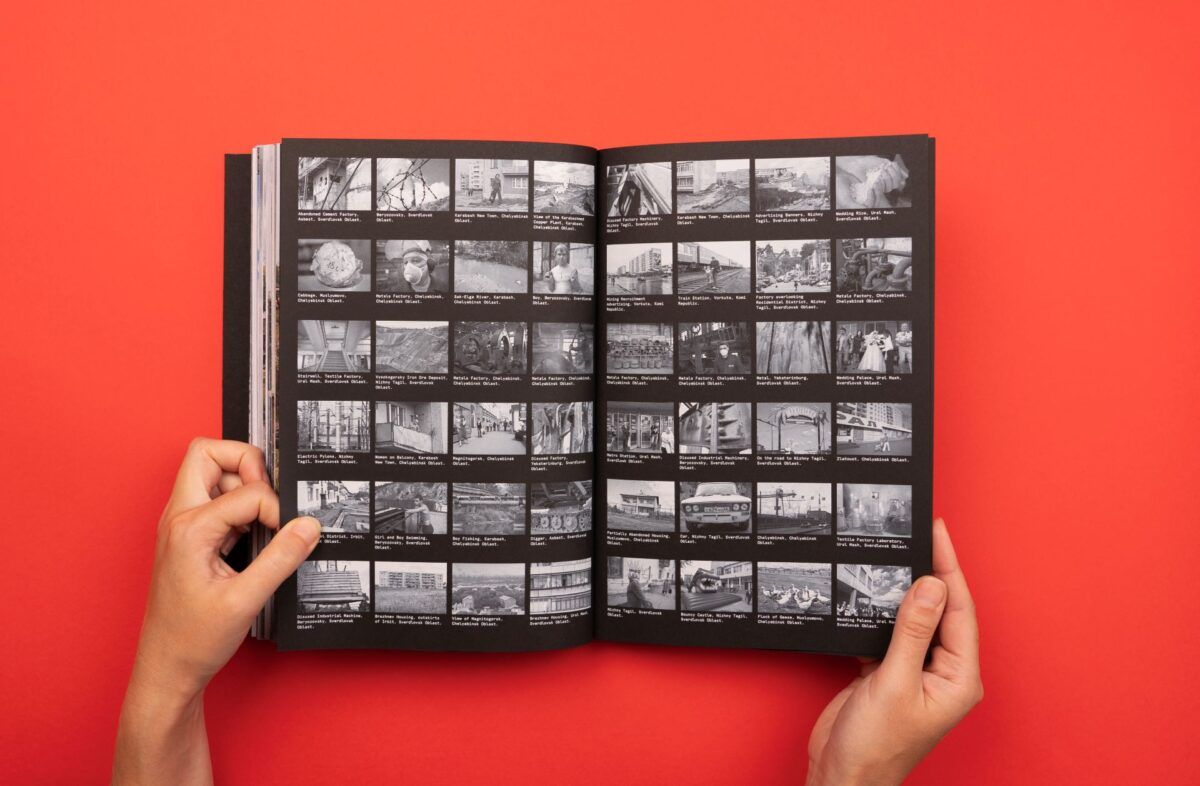

The contact sheet style thumbnails were a practical choice in they allowed us to avoid including captions on the images, but we also liked the idea of showing all the images together on a few pages, rather than only in pairs.

CJ: The cover and typography – Emily experimented with some cover options, we felt we wanted to work with someone who used letter press on an industrial level and we all like the work of Anthony Burrill. We were very happy he agreed to work on the book and even better the Russian font letter press had been sourced from a group on Moscow called Partisan Press, I think Anthony had worked with them before. At the time of the war breaking out Partisan press were pasting up stop the war posters. Anthony Burrill delivers a strong message using typography and we wanted that feel for the book. We have made accompanying posters using just typography. Also, the old Russian books we looked at in the past worked this way employing different skill sets and tools.

CB: The book is partly Alan’s photography and partly homage to the grand history of Russian propaganda art. Where did that decision come from, and why? What did the creative process involve when merging the two concepts in the book?

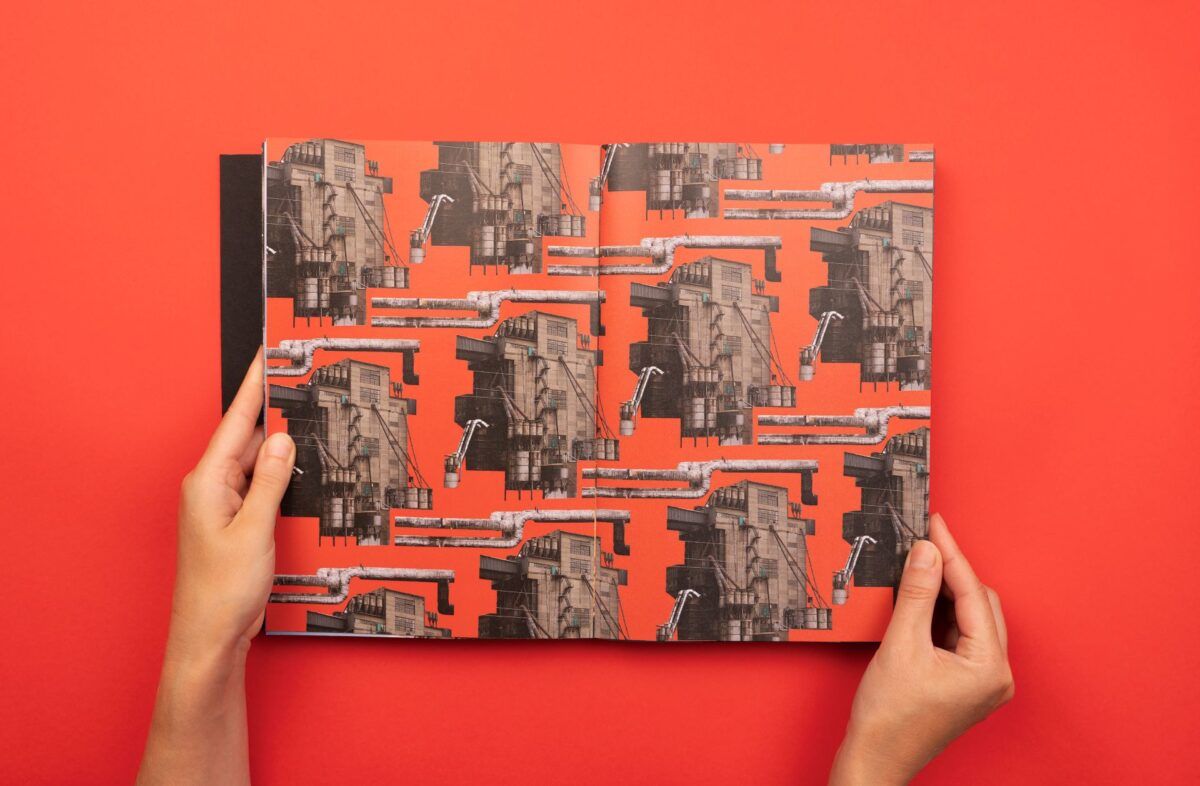

JC: We decided quite early in the process to refer to the history of Russian propaganda art. We were influenced by Gerry Badger and David Campany’s History of the Photobook and The Soviet Photobook, 1920-41, by Mikhail Karasik. We viewed those earlier books as reflections of the optimism of the period of industrial expansion. We saw Alan’s work as reflecting the unravelling of the Soviet industrial project and thought that our book should reflect that. We are sending you the brief that we wrote for Emily, describing our ideas for the book, most of which centre on the idea of unravelling, dismantling, fragmentation, and decay. The wallpapers are a visual representation of fragmentation, taking pieces from Alan’s photographs, like the cog, and repeating them in a wallpaper design. Wallpapers were used in Soviet propaganda books, but in our design, we use the device to emphasize the dismantling of industry and with it, of the society that depended on it – what is a cog when separated from other cogs? The machinery grinds to a halt, things fall apart.

The pullout with the people and buildings towards the beginning of the book is an homage to the practice of including complex montages in Soviet photobooks. While those earlier montages celebrated the power of workers and the triumph of machines, ours shows people headed to work in drab, run-down, polluted environments, the exhausted inheritors of a defunct industrial economy.

CJ: Around this time, I was also following and aware of other photographers and artists using collage and montage to express their story political ideas eg. Scum Manifesto – and Melville the Third on Instagram.

CB: RRB already was a socio-economic project that has a through-line with much of Alan’s other work, but what do you think now that it has such an important role in a geo-political way? Is this important to you personally, or for the legacy of the project?

JC: While working on the project we developed tremendous sympathy for the largely overlooked Ural industrial workers, so far from the Russian millionaires who profited from the fall of communism. They have been abandoned by the state to their failing polluted towns, left to struggle with the economic and environmental legacy of the Soviet industrial era. Ironically, the war with Ukraine will have provided welcome investment to the military factories in the region – alleviating poverty for the people living in those cities, but promising death and destruction to the people of Ukraine. This only serves to underline the complexity of geopolitical relations and to remind us of how much in world politics is unpredictable.

We have often reflected on the fact that we edited the book with a certain expectation of Russia’s further integration into the world economy. We saw things going in a particular direction and did not anticipate an about-turn that catapults our relationship with Russia back to the Cold War. The signs were there that Putin was becoming increasingly despotic, but we saw them as an internal rather than an external threat.

CJ: On a personal level, having worked in the way Alan does and edited many photo essays that work in the way Alan has, I am super proud a book like this exists, highlighting this way of working, I spent a chunk of my career working on publications like 8 and at Reuters where a type of documentary street photography / photojournalism had and has space. I have piles of old copies of Life and Picture Post which was also a format for this type of work. It’s so good that the world of photobooks has grown, and documentary projects are out there, but I feel we should push through again to build this approach up again, we are seeing this with the rise of British Culture Archive, Cafe Royal Books books and the ‘Documenting Britain’ project when it was thriving. I feel this type of work can connect us. I feel very strongly about this way of working and the freedom to do so. Every time we got the wobbles about the war, we took our minds back to the humans underneath all the politics and the worlds many of us will never see.

CB: What advice would you give to someone who wants to take on projects like this? And if you could give one piece of advice to your younger self at the start of your career, what would it be?

CJ: When I meet younger documentary photographers who ask me this, as in how I start a project like this, how does this happen. I tell them it takes time and if you have a burning desire to work in documentary keep a hold of it and don’t let anyone put out your flame, they will try. If you have money, it’s tough to keep focused as you will have to juggle making money to live and keep making the work. If you have money, it’s still extremely hard, you have to be committed to the stories you make and the journey. There will / might be gaps when work comes in, don’t give up, always keeping looking and thinking about the world around you. When I left collage there was no social media I had to phone people, I reached for the top first and it worked. Network and don’t be sacred of nos. I was nervous. I would say aim high people that seem far away will help, some won’t, some people might be rude and horrible, more nice people out there, don’t let negative situations bother you, try and learn from them, it will lead to a door opening. Social media has made it easier to get work seen, it helped us reach a global audience in a new way.

To my younger self, to trust my instincts more, and don’t let people grind you down. Things may take time so breathe and enjoy the journey.

::

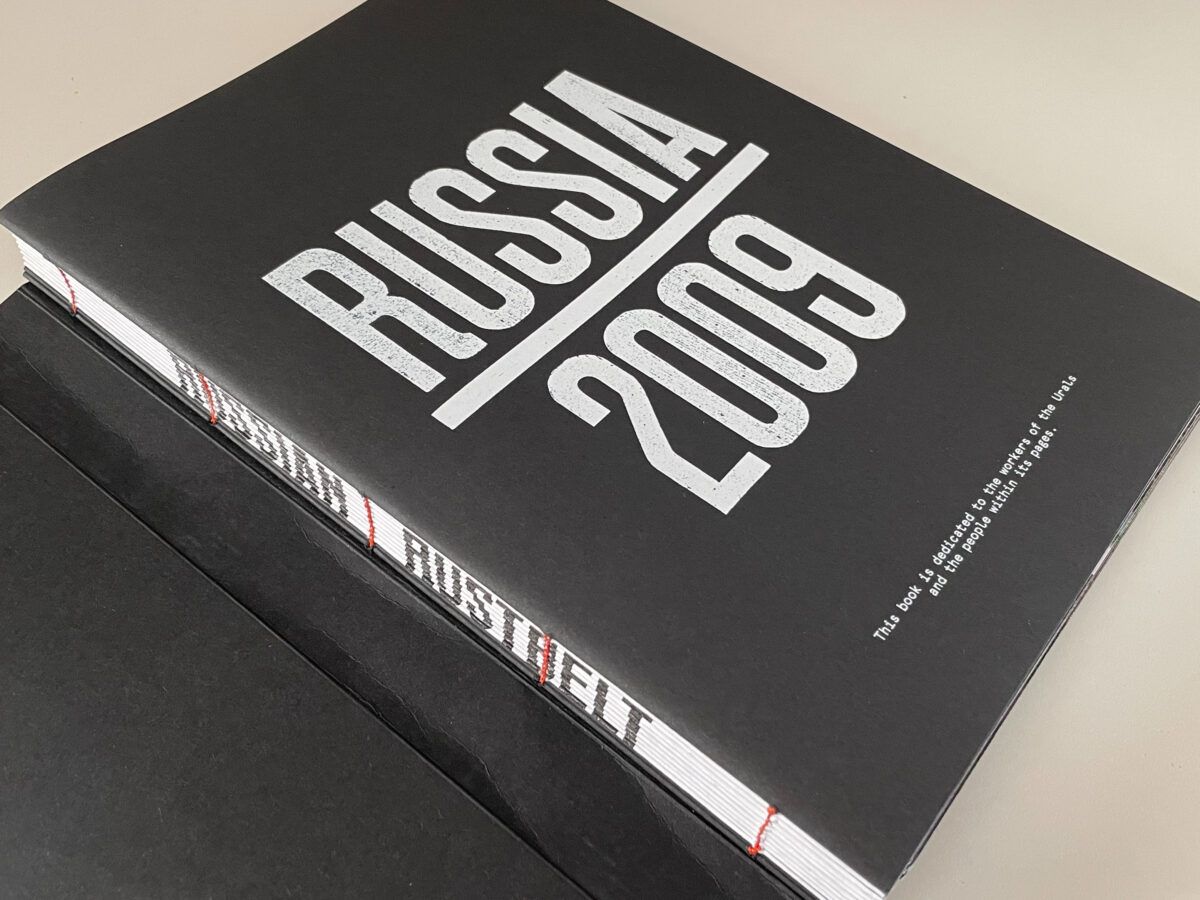

Russian Rust Belt

by Alan Gignoux

Edition of 100

186 x 277 mm

Handbound

264 pages including foldout pages distributed throughout the book

182 colour photos in total (excluding covers)

4 colour “wallpaper” pages

1 foldout montage

Essay and texts: Jenny Christensson

Photo editors: Alan Gignoux, Chloe Juno, and Jenny Christensson

Designers: Emily Macaulay at Stanley James Press, Chloe Juno, and Jenny Christensson

Photomontage and wallpapers: Emily Macaulay

Typography: Anthony Burrill

Front and back cover screen print: Another Fine Mesh, Lewes

Book binding: Emily Macaulay

Titles typeface: From the collection of Partisan Press, Moscow

Printers: One Digital, Brighton

Editor: Alison Bracker

::

Alan Gignoux has been working as a professional documentary photographer since 2000, working as a stringer with photographic agencies such as Reuters and Associated Press, and as an independent photojournalist. Gignoux has completed residencies with the NCAA in Russia, and The Rucka Centre in Cesis, Latvia. His award-winning work has been exhibited all over the world. Born in the United States, Alan now lives and works in London, England. Visit his website at https://gignouxphotos.com/

Location: Online Type: Book Review, Interview

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply