blog

Interview with featured photographer Eric Kunsman

585.235.9196 – Grape and Orange Mini Mart, 111 Orange Street, Rochester, NY 14611

While I was reviewing the submissions for our Issue #124 – Cities 2024, I immediately recalled Eric Kunsman’s ongoing work in his project ‘Felicific Calculus’ and ‘Life-Lines Throughout the United States’. I know the multiple layers of this work would apply to the theme of ‘exploring cities’ (which it absolutely does), and also highlight aspects of socio-economic aspects of where we find ourselves as a society in the 21st Century.

Smartly considered and photographed images of payphones really speak to my own personal sensibilities. I can fully appreciate a photographic series of manhole covers, trees, mail boxes, walking paths, and yes – payphones. I can also fully appreciate the underlying concepts Kunsman addresses when elevating the section of American society that relies on payphones as a lifeline due to conditions which oftentimes place them in an income bracket which is way under the economic poverty line.

Kunsman’s work prompts the viewer to challenge their assumptions, and ask more questions. How does one judge someone who isn’t able to access technologies available to citizens who are considered ‘normal’? What does ‘normal’ even mean? What biases come into play when considering users of payphones? Drug Dealer? Suspicious behavior? How else can viewers use the mapped locations to draw other conclusions, ask more questions? Kunsman’s work gives rise to these important issues, and we are honored to present his work as a feature of this issue.

::

Cary Benbow (CB): What inspires your art? What kind of stories do you wish to tell?

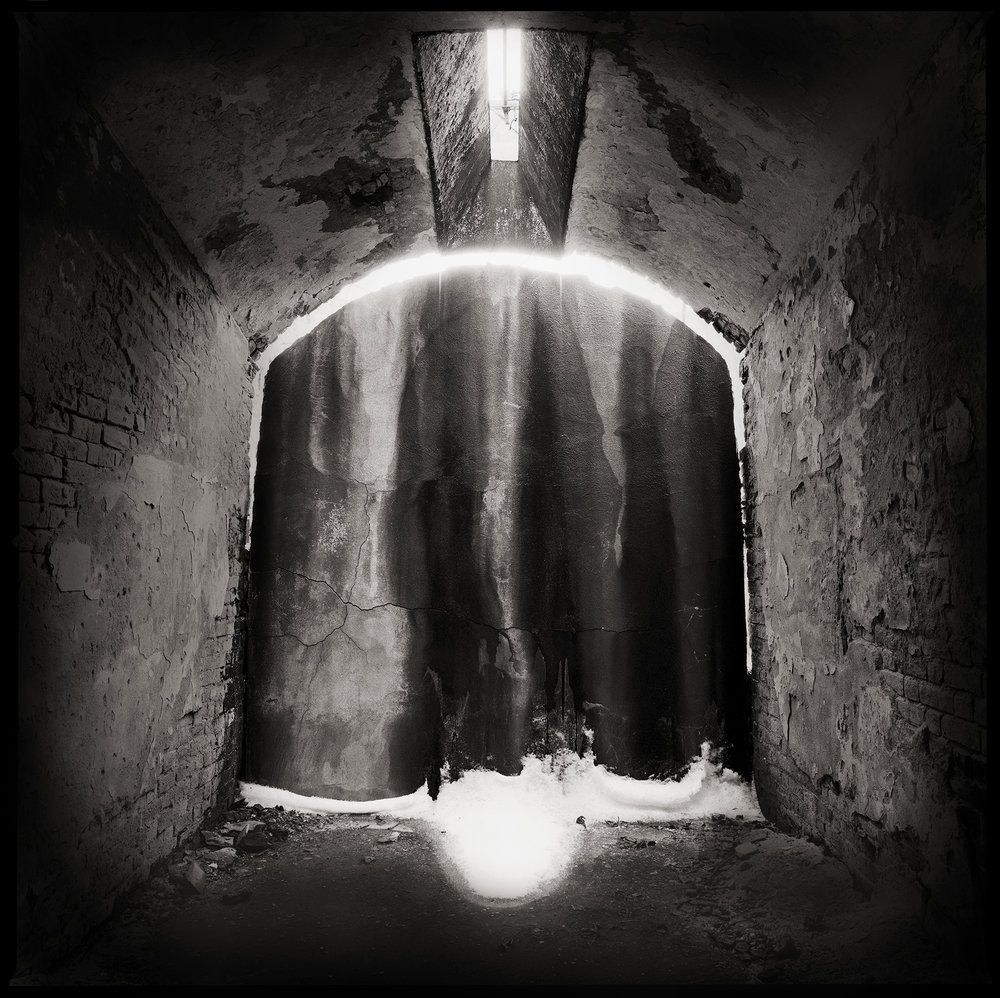

Eric Kunsman (EK): My work is inspired more by reactions to different environments I’ve been in. For instance, my work titled Thou Art… Will Give… was inspired by the original warden’s logbooks from the 1820s through the 1840s from the Eastern State Penitentiary. I would read 4 to 6 pages each day before I would go in and photograph while reflecting on those pages. I spent over 360 days photographing in the Penitentiary over a three-year. Another project of mine is the Fake News Archive Project, which was a reaction to my son, when he was in first grade, having a mock election in school because the kids were debating Hillary versus Trump. This inspired me to start taking screenshots of CNN, ABC News, Fox News, NY Times, and Washington Post every day during Trump’s presidency, and it became a set of 15 books, each over 500 pages at 12”x18”.

My latest series, which is about documenting payphones, started in Rochester, NY. Initially, I focused only on Monroe County, NY, because I moved my studio to a different area that a lot of my colleagues and friends were labeling a war zone. I then tried determining why they judged the region and its people. I observed three things as social markers: corner stores, neighborhood bars, and an abundance of payphones, so I started documenting the payphones. Then, I began to look at the relationship of the socioeconomics, and I was educated on the fact that people were still utilizing payphones in 2018. This developed into an extensive project that is still ongoing and has now expanded into chapter 2, which is titled ‘Life-Lines Throughout the United States’. I have been documenting as I travel for my exhibitions or portfolio reviews throughout the US, and I’m lucky enough to have photographed in over 20 states at this point.

This is why I feel that I’m more of a reactionary photographer than somebody who comes up with an idea and then tries to execute it. I have several other projects I’m working on, and again, these projects are still ideas that I’m reacting to and trying to flesh out. I have no true definition or artist statement about them at this point.

(CB): The ‘Felicific Calculus’ project is about much more than the casual observer may realize at first glance – and your artist statement on your website goes into greater detail about the idea behind the project. Yet many people can enjoy the work because of the anachronistic nature of images of payphones… how do you reconcile the multiple ways viewers engage with the work?

(EK): Yes, my project, Felicific Calculus, which is recording the payphones in Rochester, NY, is much more than photographs of obsolete technology. My approach to educating people is through my exhibitions, discussions, and publications to get the work out into the community and not only live within the gallery walls. The debate about the issues my project brings up needs to be started between everyone from all walks of life, as many people are losing access to communication. If the work piques someone’s interest while viewing it as obsolete technology with beautiful compositions, lighting, and all the technical control I’ve learned through my career. I see that as a gateway to hopefully having them visit an article or my website to learn more about the project’s purpose. On my website, people can see maps that compare different socioeconomic data within Rochester, NY, in relation to payphone locations. Individuals can also see my videos of my collaborators, who are social scientists, discussing the statistics of the poverty situation in Rochester, NY, and some of the research methods being used.

This only comes forward by talking to different colleges and university groups, where I like to exhibit, and having discussions with students from sociology classes, photo classes, and other related social science courses.

One of my concerns is thinking outside the box on how we get the community to engage in each of the exhibitions on a visual story that may have a disconnect to their region. That’s why, for each of the seven solo shows I’ve had for this work, we have a community collaboration where we ask the community to go out and photograph different social markers. Until now, each community has had enough payphones, so we have focused on payphones. Individuals will submit their photographs, which are printed and added to the gallery walls, along with cross streets or addresses so that we can later map that area payphones and have an open dialogue about some of that community’s biases by which places they visited more often.

Again, for me, the photographs are an entryway to start the discussion, and without the discussion, the pictures are meaningless and become beautiful images of obsolete technology. Therefore, it is my responsibility to ensure that the conversations are starting, and I have also used social media as a platform to do so.

Because I’ve been educated, my team of collaborators is creating a project called ‘Good Phones,’ which is taking old payphone housings and converting them to free phones for those needing access to communication through Voice Over Internet Protocol (VOIP.) We will provide free voicemail accounts across the entire network that individuals can access on any of our phones. We are focused on breaking down some of the race and class barriers associated with using payphones.

Unknown Number – ACE Cash Express, 3150 Gentilly Blvd, New Orleans, LA 70122-0218

(CB): How does the work in ‘Felicific Calculus’ or ‘Lifeline Throughout the United States’ relate to your other projects? For example, how are they similar or different to your project ‘Loss of a Memory Warehouse’?

(EK): The body of work in this issue is from chapter two of the payphone work, titled ‘Lifeline Throughout the United States’, which is an expansion from Felicific Calculus, which was only focused on Rochester, NY. Since I started photographing again in 2012, much of my work has focused on social economics within the Upstate/Western New York region. I state that I started photographing again because from 2005 to 2012, my sole focus was my business, Booksmart Studio. I did not take a single photograph during that time, but it also helped to influence how I perceive socioeconomics and the stress of owning a business in the area where I live.

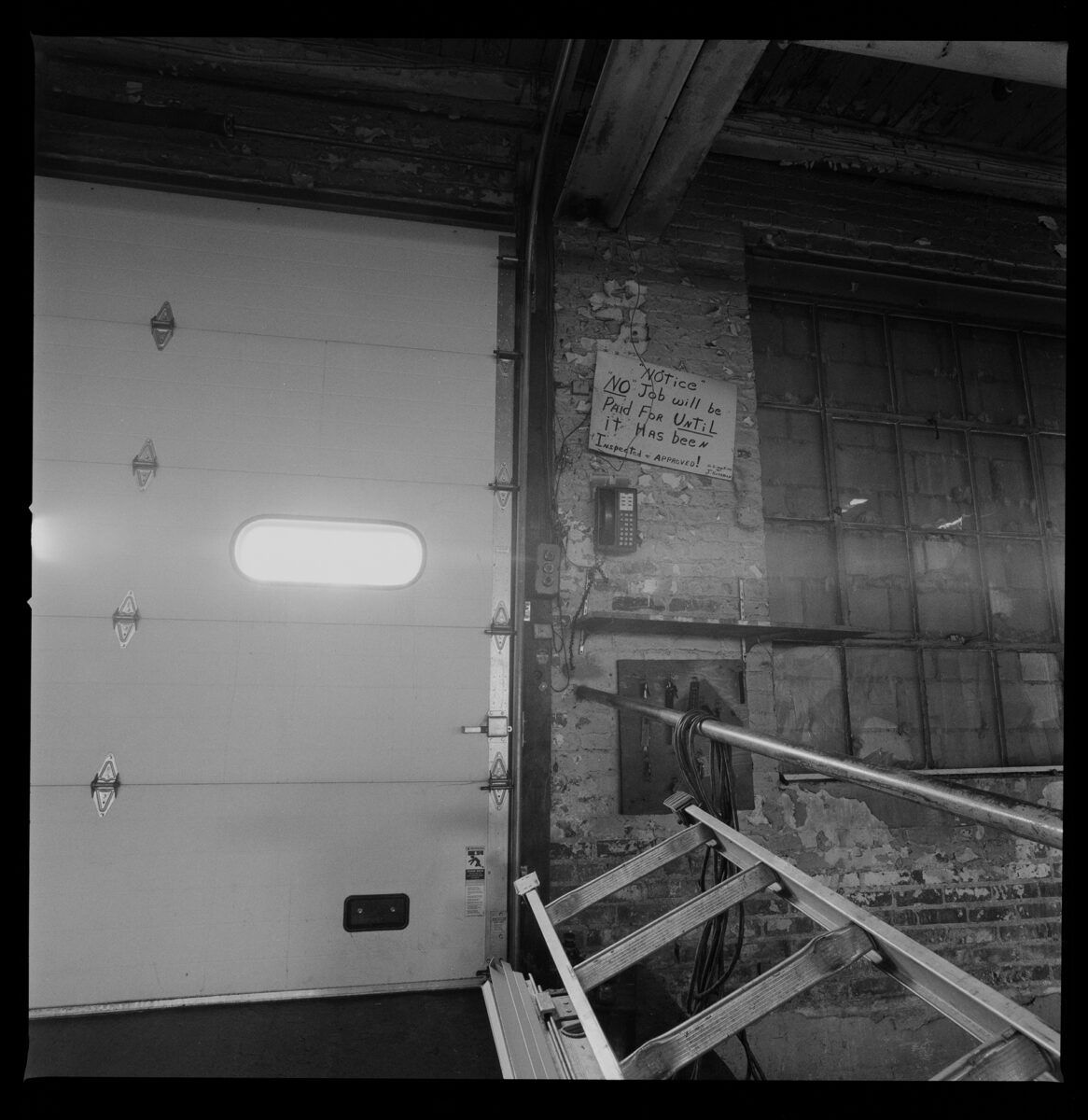

The project you discussed, ‘Loss of a Memory Warehouse’, is very personal. It is about my family’s roofing company, where I grew up working from 4th grade through college, helping my grandfather and father on roofs. That’s where I learned to work, and my parents supported everything I wanted, along with my brothers and sisters, as we grew up. However, in Bethlehem, PA, around 2010, a casino was put in the former Bethlehem Steel location, and my parents became hooked on gambling, which caused our family very serious distress. The ‘Loss of a Memory Warehouse’ was photographed in less than two hours as I was trying to help my father clean out the warehouse before it was seized due to issues that derived from gambling. Over three days, I learned the seriousness of the problem, and it was a way for me to digest what I learned and provided a different perspective on my childhood, where I was cared for and provided for by my parents. Therefore, in those three hours, not only was I photographing, but I was also digesting and packaging my childhood memories of where I learned to work and truly understand the value of family.

(CB): How do you generally describe your photography to someone who’s not familiar with it?

(EK): If somebody is unfamiliar with my photographs, I describe myself as being either a social documentary photographer or a visual sociologist. The reason why I say visual sociologist now is because my pictures have much more behind them than just being photographs and often have data accompanying them at this point. A few curators have labeled me as a romantic social documentary photographer because I don’t hit people over the head, and often, the photographs can stand as individual images that are softer than most social documentary work at this time.

From ‘Loss of a Memory Warehouse’

585.266.9536 – RJC Susville Laundry, 709 Titus Ave, Rochester, NY From the series “Felicific Calculus: Technology as a Social Marker of Race, Class, & Economics in Rochester, NY

(CB): Of the times you’ve shared/shown your work so far, what exhibition had the biggest impact on your career, or left a lasting impression?

(EK): This sounds like a generic answer, but honestly, any exhibition that I’ve been able to personally attend, either the opening or closing, has had an impact on my career. I’m the type of person who likes to have the curator control the exhibition’s narrative and create a unique exhibition for their space, and when I show up, I learn something new about how people perceive my work. This also allows for further discussion about what people are seeing and has helped me grow as a photographer and human being. The talks with classes or individual discussions at the openings are always enlightening. I get to learn not only how they see the work but how it may influence them and reflect on their own stories, and that is something you cannot learn from books or online and can only come from genuine discussions. If I cannot attend an exhibition, I’m missing out, and the exhibition is superficial without personal growth for me, which is why it is so important to participate in any solo show of my work.

(CB): Tell me about your background in Printmaking/Book Arts – how does it inform your photographic or creative processes?

(EK): My printmaking and book arts degree from the University of the Arts taught me how to slow down and enjoy the process because it was the opposite of my education at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). I often joke that the two educational institutions forced me to utilize my left and right brain. This is because of the different ways of thinking, whether about technology (the left brain) compared to thinking about the process and conceptual reason (the right brain). I’m utilizing the book arts & printmaking degree in my photography practice through my studio. Within the walls of my company, Booksmart Studio, we have many wide format printers, a bookbindery, and a darkroom where I still work with film for all these projects. I would not be as successful if I didn’t slow down to enjoy the photographic process and pause to think about what I photographed, as I am waiting to see if I created the concept once my film is processed. That reflection time is why I say it slows me down. Yes, I take fewer photographs when I’m working with film compared to working with the digital camera, but for me, it’s that time of missing the latent image that slows me down and allows me to think critically about why I created that photograph.

Many people don’t realize that I also still print historical photographic processes such as Kallitype, Platinotype, Platinum, Gum Bichromate, and other processes within my studio for my landscape photography. Most people do not know about it because they now see me as a payphone photographer. My company, Booksmart Studio, ultimately combines my degree from RIT and the University of the Arts. When you walk in the door, you can see that instantly, as in the bookbinding area, everything is done by hand. I have complete control over color management in the wide format area, which I teach at RIT. I manage our color management in-house within every facet of my studio and help other print studios. Finally, the darkroom allows me to work in any process I wish, and I am fortunate to be able to produce any work that I could imagine, all under the roof of my studio.

(CB): What impact or influence does being an art educator play in your ‘role’ as an individual artist? Or do you pigeon-hole these different aspects of your life into different categories?

(EK): I don’t pigeonhole the different aspects of my life because my students influence my work and my family. Everything for me is a reaction to my mood for the day or week. What’s important to me each day is that my kids are going through different stages of life, and I need to illustrate my concerns and passion for them. My relationships within my community, school, and house inform my projects.

After all, if it weren’t for my colleagues and friends, my project on the payphones would have never started because I was trying to learn about the labeling that was being applied to individuals they’d never met.

The fun part about being an educator is that since 2005, I have yet to teach photography or at least the mechanics of photography at RIT. I teach things that are more printing-related or geeky things, like the color management classes, which is why I don’t get burned out about photography. However, my fine-edition printing class at RIT is the back end of photography, which is how we convey our message via the printed form once we’ve created the photograph. This is something that is not only for my students but also for my clients at the studio. I often demonstrate how a viewer will interpret why a photographer meant to take a photograph through the print, but while utilizing the digital darkroom, are you bringing that idea forward using the same tools we had in the darkroom? A few of those tools, such as contrast, dodging and burning, and color correction, are as important today. We have much more control, but we must use it properly. I feel this is one of my greatest assets as an educator and collaborator with other photographers and artists within my studio walls.

One of my favorite assignments for my students is having them swap RAW files randomly with another student. Then, the student must look at the image and analyze why they believed one of their classmates had taken the photograph and what they were trying to bring forward in its meaning. They work on the file utilizing digital darkroom techniques to try to bring that perceived message forward, and it is eye-opening for everybody in the classroom as each person must explain why they processed the image in the manner they did.

As an educator, I establish that we are all peers and that the only difference between my students and me is 22 years of experience in the photographic field. I emphasize that we are all there to learn from one another, as I still learn from my students. After all, sometimes they get to show me some of the newest features on my iPhone or the latest operating system from Apple. The students at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf, where my full-time position is housed, also show me ways to improve my ASL skills. Ultimately, we are all just peers trying to build relationships to help further society and our practice of being photographers.

585.232.9542 & 585.232.9262 – Busy Bee Restaurant, 124 West Main Street, Rochester, NY 14614 – City Newspaper

The Drapery – from ‘Thou Art… Will Give… ‘

(CB): Which artists have been most important to you, and what or who are your inspirations?

(EK): From an early age, Walker Evans was the historical photographer who was most important to me, followed by the work of W. Eugene Smith. Yes, I look at other photographers’ work, but those two photographers truly encompass the way that I visualize my final prints and images.

Two photo educators from RIT who have been influential in my work are Willie Osterman and Owen Butler. Each of them has helped with various forks in my photographic education career. However, the most influential person in my career and life was Lou Draper, whom I had the privilege of studying with for one year at Mercer County Community College. I learned more about myself as a person and human being in that year than in any other period. I credit Lou with being the photo educator, photographer, and human being that I am today because I don’t think I’ve ever respected another person in my life as much as I did Lou. Lou was not only an incredible photo educator and photographer, but he was also a very supportive person. He helped form Kamoinge, which has been very important to black photographers for decades. He was instrumental in many photographers’ careers through that organization and his classroom.

(CB): So if these photographers have qualities that you admire/desire — how does that ‘inform’ your own creative process?

(EK): Lou Draper is my answer to the type of person and educator I aim to be. I often have Lou in the back of my head while photographing because of what he would say in critiques about composition, framing, and the final print. He would emphasize how one needs to be aware of and control every aspect of one’s visualization, which then controls how the viewer moves through the frame of one’s photograph. Unfortunately, Lou passed away early in 2002, and I lost him as a mentor. I could only imagine if I was still able to have his advice for the past 22 years, how much more I would have grown as a photographer and person.

(CB): What advice would you give to someone who wants to take on projects like yours? If you could give one piece of advice to your younger self at the start of your career, what would it be?

(EK): Honestly, the advice I would give somebody else who wants to create projects like mine would be the same advice I would give myself when I was younger. Allow your photographic process to develop on its own and share it as you create the work to learn from other individuals you can have conversations with and even disagreements with. I beat myself up for a few years when I didn’t take any photographs because of my studio, but at the same time, I was learning what has informed my work since 2012, which has become essential to the way I am documenting the subjects that I am at this point.

All my decisions, whether correct or wrong, have got me to where I am today, and I am enjoying the community I’ve been building, whether it’s photographers, social scientists, librarians, or the general community. The individuals I engage with daily, even those with minimal conversations, have allowed me to self-reflect and create the body of work I have up until now. I know it sounds generic, but sometimes we cannot overthink the decisions that we’re making because no matter what, in the end, they lead us through our life and inform us about our artistic practice as our life has a direct influence on the bodies of work, we all create. So, enjoy the ride and look at what other photographers are developing, but make sure that you are producing work that is important to your concerns and beliefs, and be true to yourself and your values.

::

Eric Kunsman is a photographer and book artist based out of Rochester, New York. Eric works at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) as an Assistant Professor in the Visual Communications Studies Department at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf and is an adjunct professor for the School of Photographic Arts & Sciences. Eric is as drawn to the landscapes and neglected towns of the American southwest as he is to the tensions of struggling rustbelt cities in the U.S. northeast. He is attracted to objects left behind, especially those that hint at a unique human narrative, a story waiting to be told. Eric’s current work explores one of those relics: working payphones hidden in plain sight throughout the neighborhood near his studio in Rochester, NY. Associates suggest they signify a high crime area. This project has shown Eric something very different.

Location: Online Type: Black and White, Cities, Featured Photographer, Interview

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply