blog

Interview with photographer Nick Brandt: The Echo of Our Voices

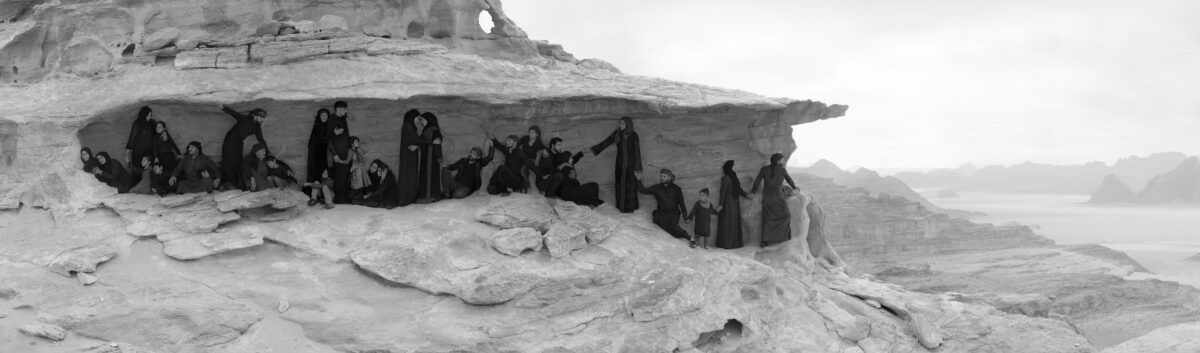

F’taim and Family, Jordan, 2024 © Nick Brandt

For over a decade, photographer Nick Brandt has distinguished himself by crafting powerful visual narratives that explore the complex relationship between humanity and the natural world. His latest project, The Echo of Our Voices, the fourth chapter of his ongoing series “The Day May Break,” turns his empathetic lens towards the often-unseen plight of displaced Syrian refugees in Jordan.

Against the starkly beautiful yet unforgiving backdrop of the Wadi Rum desert, Brandt’s meticulously composed black and white photographs elevate these individuals, presenting them as “human islands” grappling with the compounded injustices of war and environmental devastation. Through striking “sculptural compositions” featuring families posed on powerfully symbolic pedestals, Brandt moves beyond mere documentation or portraiture, offering a profound commentary on resilience, the enduring human spirit, and the interconnectedness of global crises.

His work not only captures moments of profound intimacy and strength but also shines a light on the disproportionate impact that climate change makes on the world’s most vulnerable populations. In this interview, I took the opportunity to ask Nick Brandt about The Echo of Our Voices, delving into his motivations, his creative process, and the powerful stories that lie at the heart of this deeply affecting series.

::

Cary Benbow (CB): Your work has consistently addressed the devastating impacts of environmental destruction. In The Echo of Our Voices you’ve shifted focus to displaced Syrian refugees within the context of Jordan’s water scarcity. Could you elaborate on the specific connection you see between these human stories and the broader environmental crisis?

Nick Brandt (NB): Let’s take the Syrian families in these photos as an example. They live in a state of perpetual displacement, moving up to several times a year to where they can find agricultural labor based on sufficient rainfall for crops to grow. This cycle is endless and predicted by climate scientists to only get worse in coming years.

Of course this is the same story across much of the world. And with that, you will eventually see hundreds of millions more climate refugees, forced, through no falult of their own, to find somewhere they can live and make a living.

So I believe that if the way humans operate doesn’t change rapidly, I am expressing a wider future reality.

CB: The ‘human islands’ concept is visually striking. What inspired you to use the Wadi Rum desert as a stage for these portraits, and how did you work with the refugees to create these sculptural compositions?

NB: I researched other countries around the world with deserts, but I kept coming back to Wadi Rum in the south of Jordan. It was the verticality of the mountains emerging out of the desert plains and dunes that act as a visual echo of the shapes of the families on the boxes, the way that landscape and people flow into one another that finally compelled me to use this as the location.

In previous chapters, I generally wanted the people I was photographing to present themselves for the camera how they feel comfortable, even if they’re up a ladder, or holding their breath underwater. With The Echo of Our Voices, we asked for them to work with us on frequently complex choreography that emphasised their familial ties. As a result of this, I spent my first couple of weeks in Jordan traveling around to where the Syrian families lived, meeting them, getting to know them, and only then inviting certain families to the desert for a week at a time.

I also worked with two creative collaborators that acted as choreographers, always trying to bring out or highlight the connection, the intimacy between members of the families. Each family was there a minimum of six days so as time went by, they came to understand what we were doing, and at the end of each session would come over to the camera and see what I had photographed.

CB: You’ve emphasized the irony of those least responsible for climate change bearing the brunt of its consequences. How did your personal interactions with the Syrian families in Jordan reinforce this message for you?

NB: At the end of each shoot, we always interview key people who have been photographed. You then really get a stronger sense of just how much trauma they have been through. You see their humility and grace. You realise how comfortable our own lives are. And in particular with the Syrian families, because they are already long-term refugees from war, you see how that experience has made their connection with one another still stronger.

These are people who lost their homes, their way of life, their communities, their land, everything. Now all they have is each other. It seems to have given them a strength and togetherness in the face of such adversity.

CB: Given the recent developments in Syria and the refugees’ potential return, how do you see The Echo of Our Voices evolving as a narrative? Are you planning to continue documenting their journeys?

NB: With the fall of Assad, Syria’s brutal dictator in December, obviously I thought, oh, maybe they finally get to go home. I asked Lubna, our wonderful local families researcher and coordinator, to get in contact with all of them and see what their plans were. Nearly all of them said that their homes, their land in Syria had been destroyed during the war, so therefore if they were to return, which they all wish they could, they needed to be sure there was stability within the country. So far, the signs appear to be encouraging but you can understand their hesitancy.

I would love to continue to document their journeys, but like each project, I have to find what I think is an unusual visual way of illustrating it. I also need funding, and right now, unfortunately my focus is on getting the hell out of Trump’s America to Europe after my whole adult life here, so I am not in a creative frame of mind for the first time in some years.

CB: Your work often blends stark realism with a sense of surreal beauty. How do you balance these elements, especially when dealing with such difficult subject matter?

NB: Thank you. If we just look at The Echo of Our Voices in relation to this, there was a fine line that over the course of the shoot, was very hard to pin down. On the one hand, it could just look very pedestrian – portraits of people on boxes. On the other hand, we could go too far in the other direction and the photos became too choreographed, like some weird contrived modern dance. Finding the balance was harder than we thought, and most set-ups we failed. But of course failure is an essential part of any creative process.

But for me, the real strength of the photos is in the faces, their expressions, which you just cannot see on a screen, or god help us, a fucking phone. I became a photographer to make prints, and it’s only when you see everyone’s faces that I think the emotional impact comes through. The big ‘human island’ photographs – where this kind of large scale viewing is necessary – are at the core of the series, photographs like “Women with Sleeping Children”, “Ftaim and Family” and “Mariam and Families.” And of course, The frieze-like “The Cave”, with 28 people in the photograph, really needs to be seen at 12-15 feet long.

The Cave, Jordan 2024 © Nick Brandt

CB: This project is part of ‘The Day May Break’ series. How does The Echo of Our Voices fit within the larger narrative of this global project, and what can viewers expect from the upcoming major exhibition at Gallerie d’Italia Museum in 2026?

NB: With each chapter I have no idea what I will do on the next chapter until I have finished the previous. Initially, the plan was to photograph humans and animals impacted by climate change and environmental degradation together within the same frame, a shared sense of loss. This was the part of the concept of the first two chapters.

However when it came to SINK / RISE, Chapter Three, photographed underwater, in relation to sea levels rising, it made no sense conceptually or practically to include animals. And then, to go from climate change induced over-abundance of water, it felt conceptually appropriate to move to the antithesis of that, a climate change induced desiccation of so much of the world, with Jordan being one of the most water-scarce countries on the planet.

The exhibition at Gallerie d’Italia Museum will be the first institutional exhibition to feature all four chapters. They partly funded The Echo of Our Voices, a godsend in this day and age, especially for photographic projects of this scale.

CB: The series is being shown this year at Art Dubai and AIPAD, among other international venues. What impact do you hope these exhibitions will have on audiences in different parts of the world?

NB: Well, of course in an ideal world you want people to see the work and have a blinding revelation that will change the way they live. Of course, that’s just a nice fantasy. More and more, I think that the people who see one’s work and might be moved by it are those who already feel similarly to how you do. Which is still not without some merit, because the work becomes part of a growing collective consciousness about what humankind is doing to the planet, its creatures, us all.

CB: With the recent fall of the Assad regime in Syria, do you feel there is a sense of hope, or impending change, for the people that you have photographed, and do you find it hard to work on projects that involve people in dire need?

NB: Everyone who is photographed (except SINK / RISE, Chapter Three, where the people are local representatives of those who will in coming decades lose their land, home or livelihoods to rising sea levels) has been through some level of trauma. They have survived, but their lives remain exceptionally hard. There’s a little comfort in knowing that for the days/weeks they are working with us, they are earning some much needed income, and on Chapter One, they have each year received a share of print proceeds, a kind of royalty payment regardless of whether it was the image of them that sold. But I have only been able to do that on the first chapter (all other chapters are forever very much in the red).

When all have been interviewed at the end of the shoots, the humbling, gracious thing we hear each time is this: “Thank you for seeing us. Thank you for hearing us.”

That means a lot, and I hope we can honor them all.

Laila Standing, Jordan, 2024 © Nick Brandt

Mariam and Families, Jordan, 2024 © Nick Brandt

Kamal Family, Jordan, 2024 © Nick Brandt

Ahmed Family in Moonlight, Jordan 2024 © Nick Brandt

Aisha and Mariam, Jordan 2024 © Nick Brandt

Zaina, Laila and Haroub, Jordan 2024 © Nick Brandt

Ahmed and Sons, Jordan 2024 © Nick Brandt

::

Photographer Nick Brandt was born and raised in London, where he originally studied Painting and Film. Brandt now lives in the southern Californian mountains. His work focuses on the impact of environmental destruction and climate breakdown on some of the most vulnerable animals and people as well as the natural world. He is represented by Gilman Contemporary gallery.

Since 2020, he has been working on The Day May Break, an ongoing global series that portrays people and animals impacted by climate change and environmental destruction. Chapter One (2021) was photographed in Kenya and Zimbabwe, Chapter Two (2022) in Bolivia. SINK / RISE, Chapter Three (2023) was photographed in Fiji, and The Echo of Our Voices, Chapter Four (2024) was photographed in Jordan. All the series are published in book form.

Nick Brandt will present The Echo of Our Voices in a solo exhibition at AIPAD Photography Fair (April 23 – 27, 2025) with Gilman Contemporary at Park Avenue Armory in New York. Selections of The Echo of Our Voices will also be featured with Waddington Custot Gallery at Art Dubai, followed by a group exhibition at Waddington Custot in Dubai.

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- artistic residency

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- Hom

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- p

- photographic residency

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply