"Smile!": A Polemic on Fine Art Portraiture

by Stephanie Dean

"A smiling face has more mystery than a dull face."

- Odd Nerdrum, Kitsch: More than Art, 2011

With the help of the Oxford English Dictionary and a publication called "Public School Slang", Angus Trumble was able to trace the origins of the photographic command "Cheese!" to British Public Schools in 1910. This is indeed a definitive moment in the history of photographic portraiture. This revelation was not noticed by practitioners of photography or its historians, because Trumble's book was not about art or photography, but specifically about the smile. However, Trumble's finding has historical importance and meaning that touches all of us - everyone has been commanded to smile for snapshots at least once in their life. Where Trumble places this moment in his book is compelling - he includes it in the chapter entitled "Deceit." Trumble, like many photographers, does not trust the smiling face in photographs. Commanding someone to say "Cheese!" or telling them to "Smile!" is most often relegated to the realm of snapshot photography and sometimes comes into play in photos associated with commerce, such as promotional photos, headshots or advertisements.

While many people may be annoyed, or at most indifferent at being asked to smile for photos, fine art photographers have manifested their distrust and dislike of the smile into a pervasive phenomenon which dominates fine art portraiture: the photographic preference for sitters is that they not smile for portraits. The preferred, unsmiling visage results in a sort of blank stare, or despondent frontal pose; rarely there is a hint of a smile, but never nearly enticing enough as to cause as much discussion or speculation as Mona Lisa's smile. I am presently working on tracing the origins of this phenomenon in order to discover who, when, why and how this preference was put into practice.

Considering photographic history, the celebrated fine art portraiture of today by masters such as Reinke Dijkstra, Thomas Struth and Thomas Ruff have more in common with the portraitists of the past - portraitists whose subjects had to suffer through exposures of seconds in length while being strapped into contraptions just to keep them still for a "good" exposure. The product of this was a serious, blank and forced expression. The long process aimed to create a realistic portrait of the person, but could not relate the absolute authentic likeness of the resulting photo to the actual persona it sought to capture. The photograph was generally considered more "truthful" (or considered "the truth") than a painted portrait, and the concept of "truth" in photography is still debated and doubted today.

In photographic discourse on portraiture, ideas of authenticity, purity, and the unmasking of the "real" persona — as opposed to the persona that the subject presents to the world — dominate. If there is not a quote by the photographers themselves citing the importance of Arbus or Sander, usually the authors writing the introductions to their books and exhibitions refer to or cite these masters as influences.

Most portrait photographers are suspicious of the way in which people actually want to portray themselves to the camera, and thus they discard the sitter's desire in an effort to achieve what they feel to be the most authentic portrait. This suspicion is born of the assumption that the subject being photographed will in some way interfere with the authenticity of the photograph, or at the very least they might disrupt and unpredictably influence the photographic process.

Odessa, Ukraine, August 4, 1993 (from the Beaches series), 1993.

Arbus said: "Everybody has that thing where they need to look one way but they come out looking another way and that's what people observe... Our whole guise is like giving a sign to the world to think of us in a certain way but there's a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can't help people knowing about you."1 Dijkstra quotes the Arbus statement above, and adds to it by saying "People think that they present themselves one way, but they cannot help but show something else as well. It's impossible to have everything under control.2" Of her motivations Dijkstra says, "I am looking for a kind of purity, something essential from human beings...I believe in a sort of magic.3"

Likewise, photographer Joyce Tenneson says:

A true portrait can never hide the inner life of its subject. It is interesting that in our culture we hide and cover the body, yet our faces are naked. Through a person's face we can potentially see everything - the history and depth of that person's life as well as their connection to an even deeper universal presence.4

Self-consciousness, embarrassment, and the desire to be photographed in a flattering way: all of these elements and their physiognomic manifestations creep into every photographic sitting; and therefore into much photographic discourse. Writing from a very self-aware photographic sitter's point of view, Barthes discusses his own experience posing for the camera in Camera Lucida:

I instantly constitute myself in the process of posing...In front of the lens I am at the same time: The one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art."5

Yet if we look at the photos by the photographers mentioned above, we rarely see smiles on their subjects’ faces. We would hardly question the talent and importance of the photographers and the critic mentioned above because of their extensive oeuvres, prolific book publications, exhibitions and literature that they dominate in the discourse of photography. However, we should indeed question the expressions on their sitters faces. We should ask, "Does authenticity only have one expression?" Or, "Are all smiles by nature inauthentic?"

Only Thomas Ruff has explicitly discussed not only the lack of smiling in his portraiture, but also why his portraits seem to have no expression whatsoever. Ruff feels that the expressions presented in his portraits are "normal", and that his photographs cannot tell the viewer anything about the person portrayed. Ruff has stated, "I don't believe in the psychologizing portrait photography that mycolleagues do, trying to capture the character with a lot of light and shade. That's absolutely suspect to me. I can only show the surface. Whatever goes beyond that is more or less chance."6

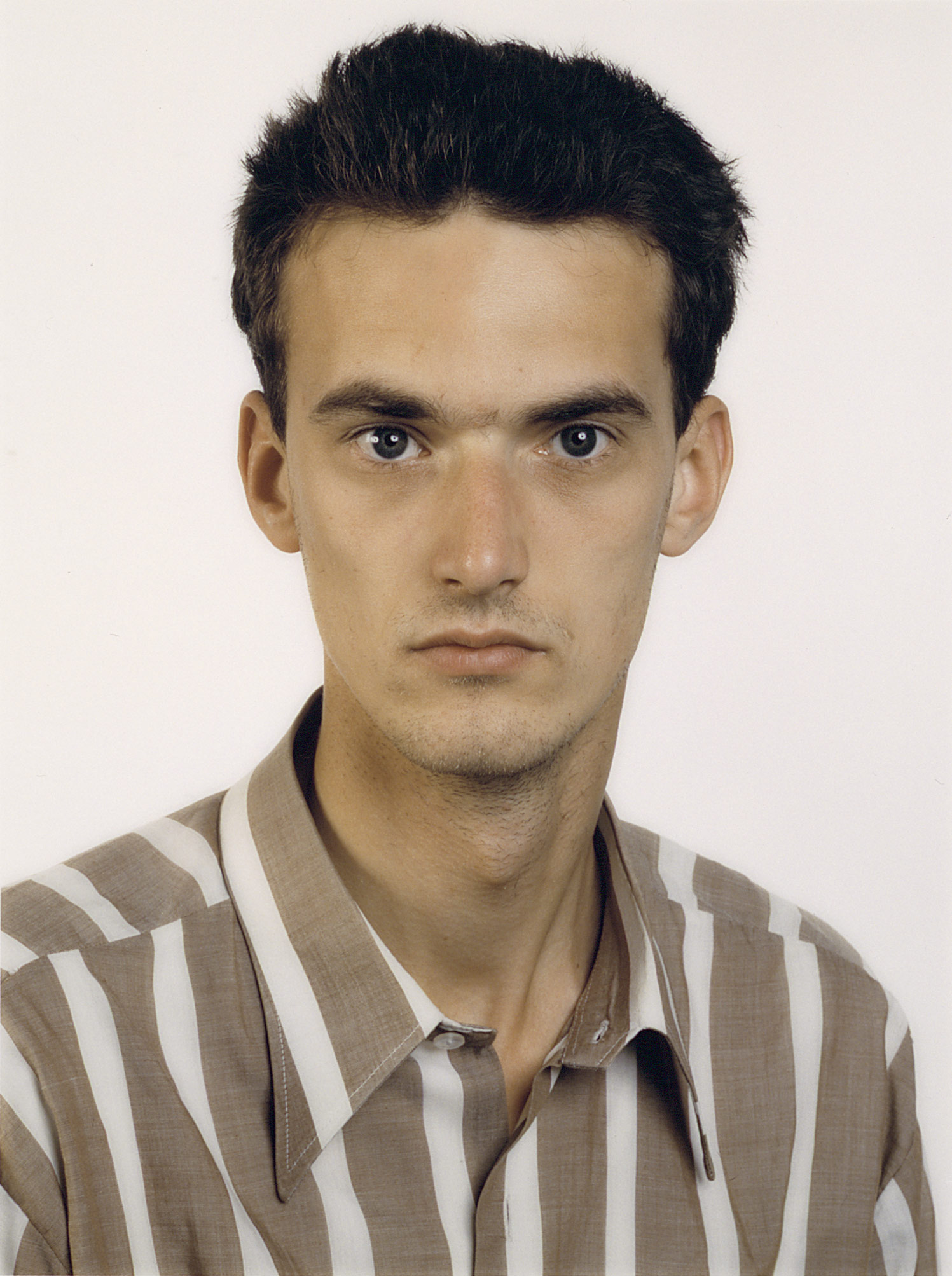

Portrait (A. Siekman) 1987

In an interview with Isabelle Graw, Ruff was asked: "Why do you ask your subjects to look serious and keep their mouths shut? On what artistic level does this choice function?" to which Ruff replied:

I want my subjects to appear normal, with facial expressions that are as normal as possible, so that the resulting photograph is "normal". Each session is a bit like a game. I'll say for example: "Hold your head up higher, don't smile, mouth shut," and they'll do it. At the same time I try to respect the person in the sense that I don't make them look ridiculous.7

In an astounding feat of philosophical and perceptual agility, Barthes is also able to describe this "game" and the current sentiment of both portrait photographers their subjects in the following passage:

No doubt it is metaphorically that I derive my existence from the photographer. But though this dependence is an imaginary one (and from the purest image-repertoire), I experience it with the anguish of an uncertain filiation: an image—my image—will be generated: will I be born from an antipathetic individual or from a "good sort"? If only I could "come out" on paper as on a classical canvas, endowed with a noble expression—thoughtful, intelligent, etc.! In short, if I could be "painted" (by Titian) or drawn (by Clouet)! But since what I want to have captured is a delicate moral texture and not a mimicry, and since Photography is anything but subtle except in the hands of the very greatest portraitists, I don't know how to work upon my skin from within. I decide to "let drift" over my lips and in my eyes a faint smile which I mean to be "indefinable," in which I might suggest, along with the qualities of my nature, my amused consciousness of the whole photographic ritual: I lend myself to the social game, I pose, I know I am posing, I want you to know that I am posing, but (to square the circle) this additional message must in no way alter the precious essence of my individuality: what I am, apart from my effigy. What I want, in short, is that my (mobile) image, buffeted among a thousand shifting photographs, altering with situation and age, should always coincide with my (profound) "self"; but it is the contrary that must be said: "myself" never coincides with my image; for it is the image which is heavy, motionless, stubborn (which is why society sustains it), and 'myself" which is light, divided, dispersed; like a bottle-imp, "my-self" doesn't hold still, giggling in my jar: if only Photography could give me a neutral, anatomic body, a body which signifies nothing! Alas, I am doomed by (well-meaning) Photography always to have an expression: my body never finds its zero degree, no one can give it to me (perhaps only my mother? For it is not indifference which erases the weight of the image—the Photomat always turns you into a criminal type, wanted by the police—but love, extreme love).8

This delicate dance between photographer and sitter always affects the making of photographic portraits. With the 4x5 view camera it is especially pronounced, where there can be no hiding of the process.

With the 4x5 a kind of trickery, enchantment or other psychological maneuvering occurs between the photographer and sitter, in order for each to catch the other off guard. Barthes' conclusion, his desire for "Photography [to] give me a neutral, anatomic body, a body which signifies nothing!" seems to have taken over photographic portraiture and manifested in the blank stares we see from "the hands of the very greatest portraitists" today.

With regards to the smile and the 4x5 camera Marc McAndrews answered Rachel Been as follows:

RB: "Many of the protagonists of your images are unsmiling and look suspicious of your intentions. Are these natural reactions, or do you intentionally look for the seemingly unhappy?"

MM: "The fact that they're unsmiling is both intentional as well as a result of the process of shooting 4x5. Shooting with a larger camera is a much slower and more deliberate process. My intentions are to create a documentary portrait and I feel that often times smiling portraits can come across as fake and contrived."9

Perhaps McAndrews feels this way because years of being ordered to "Smile!" for the camera have cultivated this view? I ask again, if we are searching for authentic photographic portraits, how authentic is the canon of fine art portraiture if it does not include the smile?

The distinct similarities between the photographs by portrait photographers that use 4x5 cameras in search of the same unmasked indexical visage, will at some point, cease to tell us about the greater human experience. Consider these photos put in the context of the entire history of photography and it's purported "true" photographic portraiture. If for the most part, everyone has the same expression, what does that tell us? Here, I return to the words of Odd Nerdrum, speaking of "Kitsch" versus "Art" as he warns: "You can run away from your own times, but you cannot run away from eternity. If you make anything, you must compare because then you can see all of your faults.10" Clearly artists know to compare themselves to others, but I question what they perceive as their "faults" within this logic. Is it really as Nerdrum asserts in his warning - does art and art photography purposely evade the infinite and eternal? Nerdrum continues on "But in Art there is no such goal, only to find the direction of the times...but bad epochs make bad decisions."11 For Nerdrum "A smiling face has more mystery than a dull face. And that is opposite for Art."12 All of the possible mystery aside, where are we to find the smiling face? Authenticity must allow for a few of them, even within an individual artist's oeuvre! How did they become so consistently edited out?

How can photographers purport to be unbiased if every photo they put forth as authentic (or not-inauthentic) portraits exclude the expressions of joy, jubilance, and – most markedly – that most misunderstood expression in photography, the smile? If we are always trying to capture the unmasked, pure persona — the way we look when we escape our composed selves in search of the self we give to others, what types of expressions are we always going to get back? Street photographers are great seekers of these unmasked moments, however their editing doesn't tell us how authentically their subjects have been captured.

Not everyone is the same, not everyone is going to "escape" to a different place. Not everyone is going to look the same when they are "unmasked." Yet somehow, everyone does seem to resort to the same blank stare in the portraits of fine art photographers.

The smile is present in fine art photography. Occasionally. Dijkstra and Struth have smiles and half smiles, (my favorite smiling portrait by Dijkstra is this — a New York Times photo of Yulia Tymoshenko13). Cindy Sherman is often cited as smiling in her photos, however, her "self-portraits" aren't really self portraits. As Julia Peyton-Jones points out "Sherman has disguised herself to such an extent that one of the most frequently asked questions about her is "what does she look like?' Pictures of the artist as herself are rare."14 The function of the smile in Sherman's photos? Irony, and more specifically the irony of a failed "mask", especially the archetypical mask that many women put on (to which Sherman is indeed trying to draw attention by revealing its artifice). The irony intended by Sherman and many photographers using the smile is a safe and useful way for this facial expression to exert it’s meaning and shed the mystery that Nerdrum allows himself to be fascinated by. However, is this the only sanctioned and safe place for the smile in fine art photography?

There are a variety of reasons why people may legitimately smile in a portrait, in addition to a variety of social circumstances, which almost compel people to smile when they are being photographed. These reasons may or may not culminate into photographic frames, or even eventually into fine art photos selected from contact sheets or memory cards. Whether they intend or pretend sarcasm or cynicism, the smiling portrait photo may be meant as satire, and is often perceived as such.

Sanctioned genres in the realm of art photography where people smile most commonly include "Found" photographs (snapshots rescued from the anonymity of non-photographers and elevated to "art" by fine artists and photographers), people of limited mental capacity often smile (as evident in the work of Diane Arbus), and projects that use the snapshot as part of the documentary process (as in the work of Nikki Lee). Of course, the snapshot itself is a safe and expected occasion for a person to smile.

Are "serious" (professional) fine art photographers really so worried that a smiling photograph would be suspected of only ever attaining "regular snapshot" status that they must ignore or censor a portrait of a smiling person? What does this act of ignoring or censoring the smile tell us (and history) about the photographer’s assumptions about their audience? Does it say that the audience was assumed to be so happy that they needed to be reminded that life is difficult and there is nothing to smile about? Does it imply that fine art portrait photographers are really in authority to enough to tell us this?

When discussing one of Struth's portraits15 Norman Bryson cites irony as one of the reasons why Giles, the male of the couple, is smiling while his wife is not:

Eleonor and Giles

The figure of Giles is difficult to read without setting in motion ideas of mental alertness and agility, a mischievous play of irony and intelligence, qualities also present in the figure of Eleonor, where they are supplemented by intensity, charisma, independence.16

The irony of an aged man, smiling, in the face of the age spots on his hands and beyond the serious demeanor of his wife, fails to be communicated by this photo. The idea of "mental alertness" is in the eye of the beholder; here, it is in the eye of the privileged viewer-author. I never would have thought that the smiling man in the couple would be lacking (or even wonting in) mental agility; which is exactly what this quote implies. Once I read this article, the possibility that the man's age had had an effect on his intellect became an option, and only then did I consider it as one of the possible reasons for the discrepancies in the expressions of the couple. Until I read Bryson's passage, I thought that Giles was smiling because he had reason – however fleeting the moment of reason – to smile. When I looked again at the photo for this project (before I read the Bryson passage), I imagined the possibility that perhaps the man had just finished saying something, or that he was holding onto a thought which he wanted to verbalize but couldn't, because he was aware an exposure was taking place. I thought this only because I faintly recalled a photograph of my grandfather with such an expression. The oddest part about this article is that Bryson does not speculate why the wife has the blank stare that she does. The blank stare, or what I personally like to call "The art stare", is so widely accepted that it is not questioned. It is even expected. Here, for Bryson at least, the blank look is filled with meaning – "intensity, charisma and independence."

I wonder: why and when did fine art photographers decide that the smile is not acceptable for portraiture? What will future viewers of these photographs think when they look back on the masses of unsmiling people in our "Fine art portraiture"? The precise moment or the trajectory of when and how this blank stare or expressionless face became the de facto and de rigueur face of fine art portraiture is the topic not only of this polemic, but also of my research, and the reason why I am surveying photographers, students of photography, professors, curators and anyone else who cares enough to take my questions seriously.

Will future viewers of our contemporary portraits have the same thoughts as my students when learning history of photography as they view the early carte de visites and Daguerreotypes: "Were people just not allowed to smile back then?".

As you ponder this topic, please consider taking the survey on portraiture that I have prepared. Just click the link and let your opinions flow.

Survey closed on June 15, 2012.

Contact Stephaniedean@ameritech.net with any questions or comments.Be Sure to visit Dean's Website: www.stephaniedean.com

~~~

Stephanie Dean is a fine art photographer who resides in Chicago, She is a professor of the History of Photography at Oakton Community College. Stephanie enjoys writing and talking about photography, and this is the first of many articles investigating the lack of smiles in fine art portraiture and portrait photography in general.

www.stephaniedean.com

1 Rineke Dijkstra and Katy Siegel, Rineke Dijkstra: Portraits (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2001), 10.

2 ibid., pg. 10.

3 ibid., pg 19.

4 Joyce Tenneson, A Life In Photography, 1968-2008. (New York : Bulfinch Press Book, 2008), 115.

5 Michael Fried, Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 107.

6 Thomas Wulfeen and Thomas Ruff, "Reality so Real it's Unrecognizable" in Thomas Ruff, exhibition catalogue, (Malmö, Sweden, 1996):104, quoted in Michael Fried, in Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 148.

7Thomas Ruff, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Thomas Ruff (Milano: Skira, 2009), "Interview with Thomas Ruff Shoot Management," 57.

8 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections On Photography, (New York : Hill And Wang, 1982), 11-12.

9 http://network.slideluckpotshow.com/profiles/blogs/interview-with-marc-mcandrews; accessed August 20, 2011 12:13PM.

10 Odd Nerdrum et al., Kitsch: More than Art, (Oslo: Schibsted Forlag 2011), 42.

11 ibid., 72.

12 ibid., 61.

13http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2005/12/27/magazine/01tymos_ready.html.

14 Cindy Sherman et al., Cindy Sherman. (London: Serpentine Gallery, 2003), Forward by Julia Peyton Jones, Director of Serpentine Gallery, 7.

15 Thomas Struth, Thomas Weski, Norman Bryson, B. H. D. Buchloh, Thomas Struth: Portraits (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1998), 129.

16 ibid., 129.