The State of Being Single: Justyna Badach's Bachelor Series

By Pamela J. Warner

Society has often been suspicious of people who live alone. Since some form of collective living has traditionally dominated housing patterns in the West, the solitary person acted as an Other onto which fears and anxieties could be projected. Much has changed, happily, in social attitudes towards people living alone, as new economic and social patterns place larger and larger percentages of the population into solitary living situations at one time or another in their lives. Justyna Badach's Bachelor Series consisting of over 50 bachelors portraits with short texts written by the photographer, explores these conventions as they relate to both individual identity and to the artistic process. Identity is constructed from within by each individual, but is also circumscribed and defined by interactions with others, first family members, then friends and eventually professional contacts. Artists, too, work out their artistic identities both in the isolation of their studios and in constant dialogue with other people, with other art objects and images. Badach's photographs attempt to make visible some of the more hidden aspects of individual identity, while at the same time representing a social moment of contact between the subject and the photographer, forcing both of them outside of their private habits.

Individuals are constantly confronted by society's ideas and conventions about what makes up "the good life" and how it should be both lived and put on display. Reassuring images of social networks such as family and close friends dominate the media, which can generate feelings of tension for people who live alone. This contrast lends a degree of poignancy to Badach's portrait of Vek. Sitting alone in a slumped posture on a stool in the middle of his living room, Vek pauses from packing his belongings. Badach's haunting prose, marked by short, laconic sentences that point to the tragic via the mundane, informs us that this is his last day here after being evicted. Forced to leave his apartment and not sure where he will go, he nonetheless allowed Badach to come over and shoot his portrait. Behind him, a lightwood folding screen that holds multiple picture frames leans against the wall. The photographs in the frames suggest a full family life: a beautiful woman with flowing hair, a couple on a beach, a child. They appear, at first glance, to place Vek into a reassuring network of relationships that would balance his distraught expression and body language, cancelling them out as merely temporary in a life rich with laughter and sunshine. Look again. The photographs in the frame are not Vek's friends and family, but in fact are the advertising photos that came with the screen when Vek bought it. Three photographs are repeated twice, framing the large central scene of the blonde woman with the horse. As marketing images to entice buyers to purchase the frame, the stock photos present an image of life lived in the company of others, where displacement and loneliness have no place.

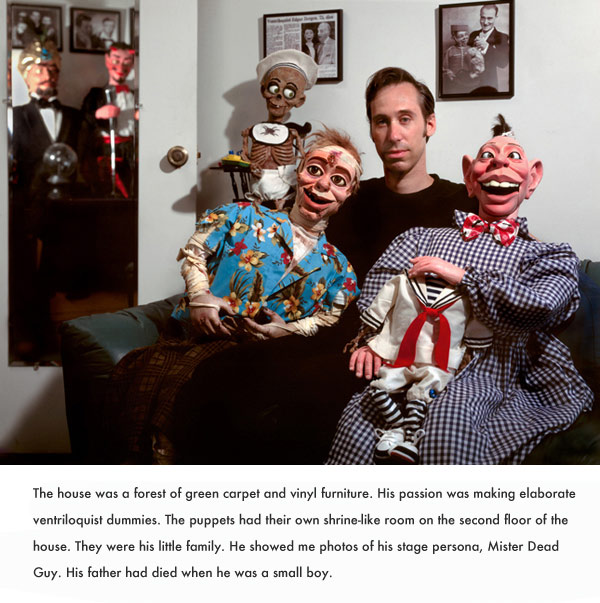

The social conventions of group portraiture inform Badach's photograph of David. Posing on the couch with three of his creations, David appears to viewers as part of an alternative family—a feeling strengthened by the vague resemblance between the puppet-maker and his creations. The soft smile on his lips, however, renders his status in this family slightly ambiguous. Do we see a father and his children, with resemblance carried on through generations, or are we instead privileged to see a man and his alter-egos, some form of exteriorized versions of himself? Regardless of how we answer that question, what do we as viewers make of the macabre overtones of the puppets themselves? The liveliness bordering on garishness of the puppets' faces contrasts strongly with David's own muted expression, but Badach insists that she is not making fun of her sitters, and suggests that any discomfort viewers feel derives from recognizing in the men parts of themselves with which they are not entirely comfortable. She points to the long tradition of the grotesque, once celebrated as an integral part of artistic culture, but increasingly sidelined by a society in which illness, deformity, and death have become taboo. The framing of the composition, in which two additional puppets observe the main grouping from their reflection in the mirror, may act as a metaphor for the distance we try to put between a comfortable sense of self on the one hand, and a complete awareness of the many conflicting aspects of our identity on the other.

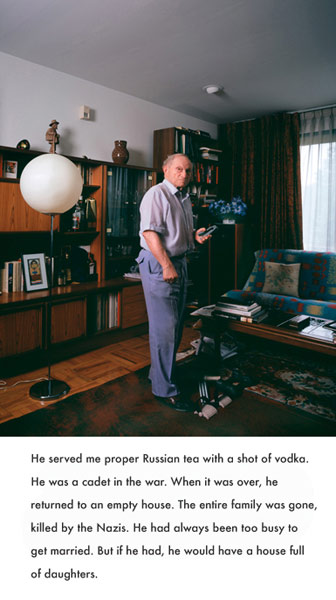

The domestic setting of these portraits gives the series an added charge. Badach refers to it as a wider metaphor for the internal life of a man, both a refuge and a prison, where people get back in touch with themselves by eliminating human contact and depriving themselves of an emotional connection with the outside world. Entering into that space to photograph it, Badach is acutely sensitive to her outsider status. "The decor of the spaces is so profoundly personal, that at times it feels like you are standing in someone else's skin, a space too uncomfortable for anyone other than the bachelor to occupy," she writes. Her texts complement the photographs. Just like the men's spaces, the voice used to write them is a highly personal one that suggests aspects of the bachelor-photographer encounter that are not recorded by the camera. Each image is the product of an experience, the emotional tone of which is defined by the interaction of two sensitive beings.

Here her work reverses the stereotypical gender construct of the artist-model relationship. Rather than a male artist looking at female sitters, we have a woman taking photographs of single men. The sexual overtones of the (male) artist's "penetration" into a (female) sitter's intimacy are absent: Badach's bachelors seem vulnerable, as she herself becomes in going to their houses, but their fragility does not turn them into objects of desire in the traditional sexual politics of the gaze. Instead, Badach manages to work the standard power relations of artists and models to a different end. The portraits, taken together as a group, narrate a series of social moments between two private individuals.

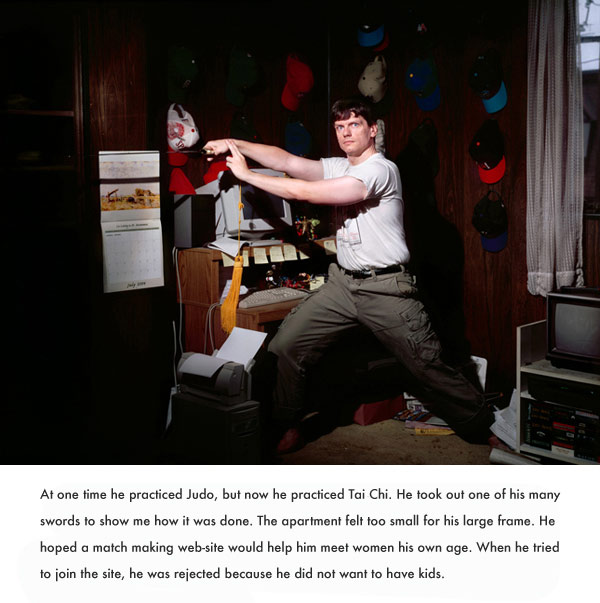

Portraits of individuals partake in social life in the way that they present sitters to viewers through the mediating eye of the artist. The portraitist makes the introduction. "Pamela," Badach seems to say, "I'd like you to meet David." And just as anyone who has been introduced by someone else can relate to feelings of self-consciousness during such introductions, so too these sitters want to project a certain image of themselves. Part of the photographer's challenge in composing such portraits is to find a way to go beyond the idea the men want to present of themselves. The models, Badach explained, if left to their own devices, would tend to want to stand with their hands in their pockets and their legs spread as if about to piss on the ground. They have absorbed cultural images of what it means to be a man and perhaps seek to reassure the viewer/photographer by assuming what they think to be a "typical" male pose. She asks them instead about their hobbies and interests, and from that conversation usually emerges a compositional idea.

Even then, however, Badach has to work to get beyond the sitters' image of themselves. Mischa, for example, wanted to show off his different arm exercises by posing in different ways with his weights and handgrips, but she rejected many of the poses as too active, working with him to get him to relax and clear his mind so that she could see past this strong projection. Richard, a self-aware model who had been photographed by Diane Arbus and spent time with Andy Warhol, has a strong narcissistic edge, a homoerotic falling in love with himself and with the beautiful male body. Rather than indulge that side of him, Badach used the mediating reflection of the mirror, not to show him gazing lovingly at himself, but rather as an object through which he engages with the rest of the world, his gaze turned to look back at her. His fascination with his own image, with posing, is still there, albeit modulated by the photographer's knowing mis-en-scène.

But Badach does not have to simply go beyond her sitters in order to discover or meet a deeper part of themselves. She has to go outside herself as well. Long drawn to landscape photography, Badach grew to feel that it catered too much to her tendency towards social avoidance. Part of the impetus of the Bachelor Series, then, was to challenge herself to interact with the men. The photographs come from a place that is not as comfortable for her as the out of doors. She chose the 4"x 5" camera for exactly this reason: she looks directly at the subject and the camera does not come in between her and the person posing. Moreover, she has to go out of her way to put them at ease through chatting and casual conversation, an exercise which leaves her drained and exhausted at the end of each shoot. The finished portrait, then, can be read as the meeting place for two beings outside their usual shells. They truly become records of a moment of encounter and perhaps self-discovery between two vulnerable individuals. In this way, they offer a more complex and sensitive alternative to the clichéd artist-model encounter.

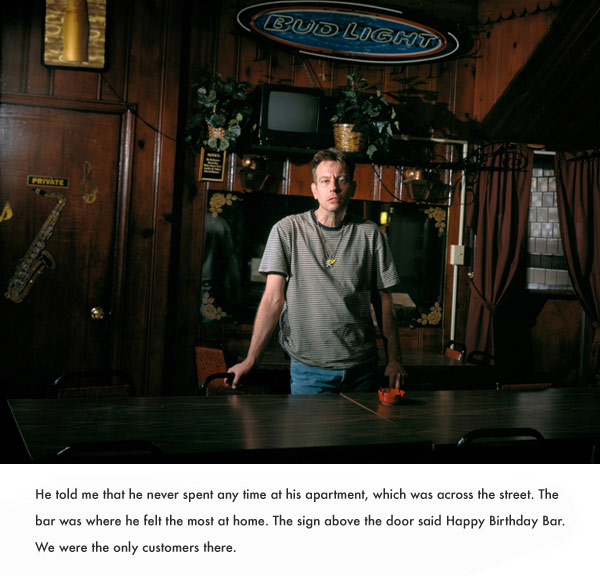

This repositioning of the tropes of artistic practices is all the more interesting given that many of the images reveal a deep visual engagement with the history of art, and with French Modernist painting in particular. Whether we see Degas' Scene of an Interior (Le Viol) in Richard or Manet's Bar at the Folies-Bergères in George, a painterly sensibility dominates the series. The drama of the Baroque infuses the dramatic lighting and pose of Jim, and the black curtain on Vek's window recalls similar devices in paintings by Caravaggio. These references to the history of art are no accident: Badach was raised by a mother enthralled by painting, who owned a complete postcard collection of the paintings in the Hermitage and who took her children to spend hours in art museums throughout their childhood. Moreover, Badach tries to bring the tactile quality so important to paint surfaces to the photographs in her choice of an albumen-coated French printing paper, which gives the finished prints a texture that captures light and lends a subtle animation to the still poses. The compositional parallels, however, would not be interesting if they did not also double back on the themes of the series: interiority and vulnerability in Degas' Interior, reflexivity and the connection between the viewer and the model in Manet's Bar.

In fact, the formal emphasis on surface and reflection also works metaphorically in relation to Badach's subject matter. In many ways, these portraits are about private worlds, which these men living alone have the luxury of developing. Normally hidden away, the idiosyncrasies of individual identity become visible in these photographs. But even these visible marks of personalities—a taste for hipster design in Matt, a fascination with tai chi in Jim, a passion for Japanese decorative arts in Richard—are themselves only surface emblems for the deeper interior world of the mind,. Notice how windows and doors in these photographs suggest but do not reveal places beyond the rooms we see. They act as portals, suggesting vistas at once external (the rest of the house, the city, etc) and internal (the psyche). Facial expressions also express the active inner lives of these men. Billy stares pensively at the floor, cut off from the clutter around him. Maneswar closes his eyes against the jumble of electronics equipment to think of something we will never know (although Badach's text hints that it's his latest crush). Manaswar's and Matthew's portraits include references to women ( the scantily clad girl visible on the television screen behind Manaswar, the bathtub pin-up behind Matthew, and therefore quietly allude to the normative heterosexuality of the bachelor. The photographs thus present intimacy even as they hint at layers of unknowable depths, suggested by the blackened, dripping eyes next to Matthew's pin-up poster. Pulsing like skin with the throb of life coursing beneath the surface (observe Mansawar's REM-sleep like eyelids…), Badach's portraits make us sensitive to the interdependent nature of exteriority and interiority, and movement back and forth between the two realms.

Nowhere is the exploration of the shifting relationships between inner and outer worlds more poignantly captured than in Badach's portrait of Kirk. Blinded from a gun wound to the head, Kirk chooses to live alone in a house that he decorated after his accident. The irony of the book on the shelf, The Evil Eye, and the blank "painting" in the elaborate gold frame on the wall (it's actually a piece of framed black velvet) suggest Kirk's critical distance from his handicap, albeit one marked with a dark dose of humor. Learning that he is undergoing experimental treatments to restore his sight does not take away the fear that most of us feel at the thought of being thrust so suddenly and entirely into the inner world of our own minds. We reassure ourselves that blind people develop hypersensitivity in other senses, such as hearing and touch, partly as a way to relieve our discomfort. Does Kirk know, I can't help but wonder, that he hasn't mixed up the white and black figurines on his shelf, or that the collections of bones share a yellow color similar to the frame on the wall? What meaning does the interior hold beyond its reassuring visual familiarity? Badach's photographs suggest other ways of knowing the world, a phenomenology of human existence that can emerge in intimate settings.

Surfaces are formed by what lies beneath them and cannot exist without that deeper support. Badach's portraits of bachelors, on the other hand, hint that the depths may not be dependent on surfaces in the same way. In contrast to trendy theories of identity that would see personality as all surface—a series of fleeting, constantly shifting, and above all un-anchored constructions, Badach's bachelors draw their strength from their rich inner worlds. In a society that has commodified and packaged social relationships into the clichés of internet dating and Vek's framed photo ads, it is perhaps not surprising, and perhaps in the end less suspicious, that these men have opted out. The series acts as a potent reminder that inner worlds can be as much a place of cultivation as consolation. Rather than illustrating a passing phase, Badach shows us bachelorhood as a valid, more permanent state of being.

To see more of Justyna Badach's work:justynabadach.com

Dr. Pamela J. Warner is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Rhode Island, where she specializes in Modern European Art History & Criticism.